Summer 2020

Eternal Victory

– Abraham Denmark and Lucas Myers

China’s view of the Korean War has not changed much since 1953. What ripples does this cause in Asia and across the globe?

The Korean War remains vital and relevant in the People’s Republic of China, even if it is often described as the “Forgotten War” in American popular culture. Although the war in China is today commonly referred to simply as the “Korean War” (朝鲜战争), in official Chinese publications and commemorations it retains the label it had in the 1950s, “The War to Resist U.S. Aggression and Aid Korea” (抗美援朝战争). Although the fighting between Chinese and UN forces stopped 70 years ago, the Korean War remains central to the national myth of the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and continues to inform multiple policy debates across Beijing in ways that may surprise outsiders.

The dynamics that drove Chairman Mao Zedong’s decision to support China’s intervention in the Korean war, and lingering memories of the War itself, have driven significant differences in how the war is generally understood in the United States and China.

In the United States, the Korean War is remembered as a costly and ultimately indecisive defense of an ally against Communist aggression, as well as the first battle of the Cold War. Yet for China, the war is viewed as both necessary to protect the nascent People’s Republic of China (PRC) from a direct threat, and as a dramatic victory for the CCP against hostile Western imperialism. For Beijing, the war has been subsequently used to justify the delay in unification with Taiwan, to reinforce distrust of the United States, and to buttress the legitimacy of the CCP as the only force that can protect China from hostile foreign powers after the so-called “Century of Humiliation.”

The Korean War remains central to the national myth of the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and continues to inform multiple policy debates across Beijing in ways that may surprise outsiders.

This divergence between how the war is understood in the West and in Beijing – both its causes and its effects – betrays broader divergences in worldviews that inflame mutual suspicion amidst great power competition.

When discussing official Chinese views on history, it is impossible to completely separate fact from politics. Historiography is often a particular challenge for Marxist regimes, because histories must reflect not only what Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels called the “materialist conception of history,” but also the regime’s contemporary ideological, political, and factional requirements. Major swaths of the CCP’s history – such as the role of the CCP and Kuomintang (KMT) in the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution, and the Tiananmen Square incident – have been revised or suppressed in order to support the CCP’s preferred narrative. As one Chinese scholar explained to an author of this article: “In the West, history never changes and the future is uncertain. But in Marxism, the future is certain and history is always changing.”

Official Chinese histories of the Korean War have been largely unchanged since the 1950s. Although scholarship on the war has certainly evolved in China, its primary conclusions have been largely unquestioned and unchanged – especially in official publications. Chinese histories still portray the Korean War as a stunning defensive victory by Chinese forces against a powerful, hostile force whose primary goal was to invade China and undermine the CCP.

Mao’s Decision to Intervene

From the onset of tensions on the Korean peninsula, U.S. officials viewed actions taken by both DPRK leader Kim Il Sung and Chairman Mao primarily through the lens of the Cold War. Just two months before the outbreak of war on the Korean peninsula in April 1950, President Truman received National Security Council Paper NSC-68, which called for the use of military force to contain communist expansionism anywhere. Washington initially believed that Chairman Mao was focused on consolidating the CCP’s control over China – the People’s Republic was still less than one year old – and on wresting Taiwan away from the Kuomintang. On October 12, 1950, a CIA memo concluded that “while full-scale Chinese Communist intervention in Korea must be regarded as a continuing possibility, a consideration of all known factors leads to the conclusion that, barring a Soviet decision for global war, such action is not probable in 1950.”

Yet contrary to these assured predictions, the CCP Politburo decided to intervene in Korea on the following day. Limited access to Chinese archives diminishes outside understanding of the intentions of China’s leaders surrounding the decision, but the opening of Soviet archives has provided a far more detailed understanding of Mao’s thinking. In early 1950, North Korean leader Kim Il Sung had traveled to Moscow to discuss his plans to invade the South with Stalin, and requested Soviet assistance. Stalin advised him to discuss the invasion plan with Mao Zedong, which he did when visiting China in mid-May. After discussions, Mao and Stalin both approved the invasion and offered some limited material support, but neither leader initially agreed to directly intervene on behalf of the DPRK.

Transforming China with draconian domestic land reform projects and consolidating the CCP’s control over the country were Mao’s primary tasks in this moment. Dealing with the remnant KMT forces on Taiwan, which Mao believed were supported by the United States and threatened to overthrow the nascent regime should the CCP falter, were a particular concern. The implications of American intervention in Korea were exacerbated by the deployment of the U.S. Seventh Fleet to the Taiwan Strait in June 1950.

Facing what he believed to be a burgeoning strategy to envelop and undermine the young nation he had founded less than a year ago, Mao acted. The following month, elements of the elite 4th Field Army had moved to Northeast China, primarily as an insurance policy against the possibility of a collapse by North Korean forces. The Soviet Union supported the idea: “We think it correct to concentrate nine Chinese divisions on the Chinese-Korean border for volunteer operations in North Korea in the event the enemy crosses the 38th parallel.”

Mao’s concerns deepened significantly in early August with the hardening of UN defenses at Pusan. He declared at a CCP Politburo meeting that a U.S. military victory in Korea would pose a direct threat to China. After the successful amphibious landings at Inchon by UN forces in September 1950, Mao’s fears of advancing American forces intensified. The prospect of a two-front war in Northeast China and Taiwan risked the CCP losing control entirely.

Facing what he believed to be a burgeoning strategy to envelop and undermine the young nation he had founded less than a year ago, Mao acted.

Ultimately, Mao saw a UN victory in Korea as the first step in an American plan to topple his regime, so he decided to pick, as scholar Donggil Kim observes, “the most favorable time and battlefield for China – namely Korea – due to its proximity to the Soviet Union and Northeast China, China’s industrial center.” In mid-October 1950, despite Stalin’s refusal of Mao’s previous request for air support over Manchuria, and his directive to Mao to not engage in a large-scale offensive against the U.S., Mao decided to ignore Stalin and intervene in Korea.

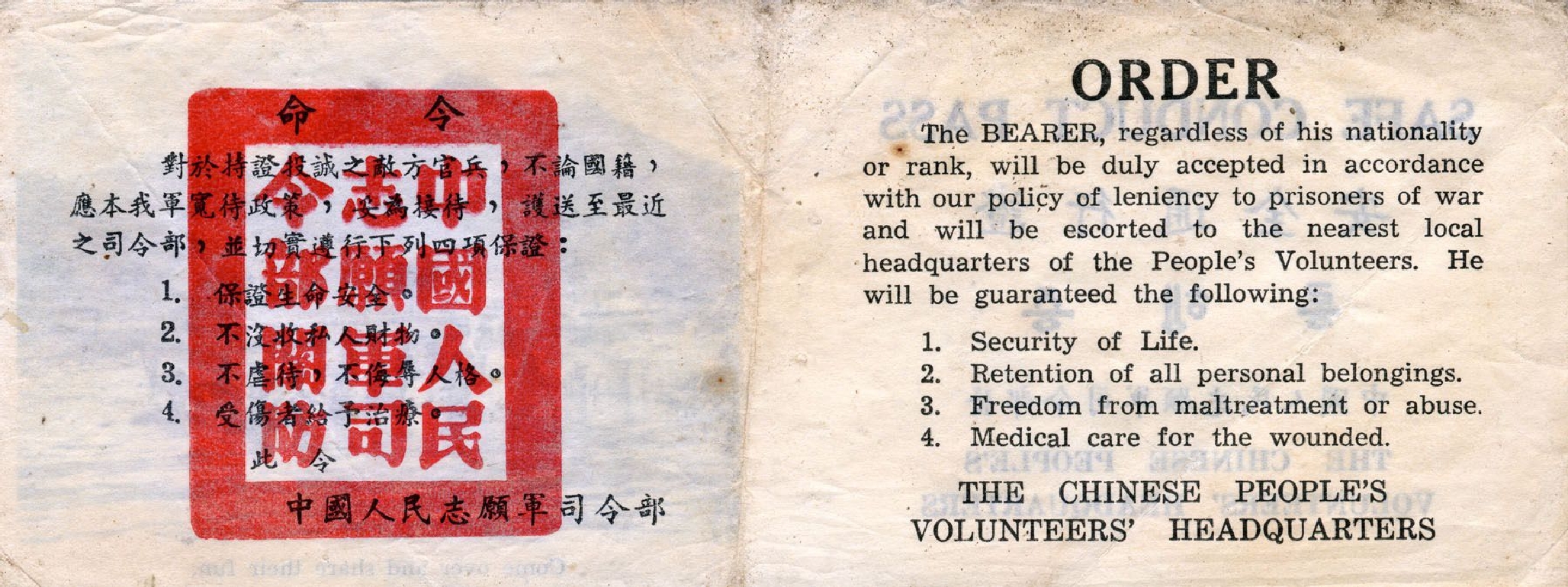

Chinese propaganda in this period echoed these calculations. Beijing called the conflict “The War to Resist U.S. Aggression and Aid Korea,” and labeled its troops as “Volunteers,” depicting the war as an opportunity to challenge American power in Asia and to project China’s rise as a regional power. More crucially, Beijing used the conflict to strengthen domestic support and legitimacy for the CCP in the aftermath of a devastating civil war, mobilize the Chinese people around the Party and the “new” China, and propel a vision of China as the driver of perpetual revolution across Asia.

Thus, a powerful confluence of the CCP’s interpretation of China’s history, assumptions of U.S. hostility, a lack of confidence in the regime’s ability to maintain power at home, and Mao’s regional ambitions combined to influence China’s decision to intervene in Korea. For Mao, Stalin’s preferences or a sense of Communist solidarity were not nearly as important as his calculation of the PRC’s security interests and his own aspirations for regional leadership – two forces he conceived of as closely related.

The Korean War in Chinese Memory

Decades later, China’s understanding of the war’s causes still differs from that of the West. The Chinese leadership remains eager to portray the war as a successful conclusion to a so-called “Century of Humiliation” and a moment of triumph for the nascent regime. This consistency can probably be attributed to the consistent utility of this narrative to CCP leadership, despite the radical ideological and policy shifts China has experienced over the decades. As shown in scholar Yuen Foong Khong’s research, policymakers invoke “lessons of history” to argue for certain policies, and these analogies in turn shape leaders’ decision-making processes by affecting their interpretation of information. Although some recent Chinese scholarship has adopted a more critical view of Mao’s decision-making and the course of the war, the overall interpretation remains altogether positive.

Chairman Mao set the tone for China’s official memory of the War by declaring it a victory. In a speech at the Central People’s Government Council in September of 1953 entitled “Our Great Victory in the War to Resist U.S. Aggression and Aid Korea and Our Future Tasks,” he declared, “we fought U.S. imperialism, an enemy wielding weapons many times superior to ours, and yet we were able to win and compelled it to agree to a truce.” Mao also argued that “a new imperialist war of aggression against China and a third world war have been put off,” and he warned imperialist aggressors to bear in mind that “the Chinese people are now organized, they are not to be trifled with.” He concluded with a warning that foreign powers may resume the war and were sure to try to subvert the CCP.

China’s official interpretation of the Korean War’s significance has remained generally consistent with Mao’s position in 1953. In the initial years after the war, Steven M. Goldstein observed that the Chinese government even blamed the severity of the war and China’s intervention on Washington, arguing that “the United States had intervened in [an intra-Korean] civil war and by doing so had changed the nature of the conflict [i.e. internationalizing it].” Writing in the 1990s in The China Quarterly, Chinese scholars Hao Yufan and Zhai Zhihai repeated this interpretation: “[The war] was the natural result of gradually developed animosity between the [CCP] and what it regarded as the foreign imperialist powers, especially the United States, and of the fear of a threat from the latter.”

“We fought U.S. imperialism, an enemy wielding weapons many times superior to ours, and yet we were able to win and compelled it to agree to a truce.”

Yet by the 1990s and the end of the Cold War, some Chinese scholarship began to incorporate more nuanced and diverse perspectives. Goldstein identified that while more traditionalist, “neo-orthodox” views blaming the war on the United States remain relatively prominent, “dominant approaches to the origins of the Korean War…dispers[ed] blame by emphasizing the impact of the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States as the causal factor in the division that created the conditions for the conflict.”

Largely driven by the work of prominent academics Shen Zhihua and Yang Kuisong, and undertaken at a time when Chinese academics had greater leeway than they have today, this perspective argues that the Soviet Union and Stalin in particular can be blamed for instigating the conflict. Both scholars argue that the Soviet Union encouraged Kim Il Sung’s invasion due to traditional Russian geopolitical interest in Northeast China and Stalin’s overly aggressive opportunism towards advancing the communist cause.

This turn towards a more context-oriented interpretation largely coincided with the warming of China-South Korea relations in this era. It also reflected the increasingly negative view some Chinese policymakers and scholars adopted towards North Korea and its nuclear program. Of course, China’s own agency and culpability in the conflict remains routinely justified.

Other Chinese analysts have gone so far as to criticize some of Mao’s wartime decisions as detrimental to the unification of Taiwan and the overall Chinese revolution. While the Korean War is still seen as a Chinese victory, Mao himself receives an occasional reprimand from Chinese historians for falling prey to mission creep and squandering strategic advantages that could have enabled a more favorable peace. Yet even these critiques remain aligned with the view that Chinese intervention was moral, largely successful militarily and politically, and intended to produce a lasting peace.

Implications for Today

As we have seen, the Korean War remains deeply salient in China today. China did not officially announce the number of soldiers killed in Korea (180,000) until 2010. Yet today the Korean War is portrayed as a glorious and successful struggle against Western imperialism and a key aspect of China’s identity as a great power.

The CCP’s founding myth is of particular significance, with the Korean War playing a central role the end of the “Century of Humiliation.” This narrative posits that China had been the dominant power in the world and the center of civilization for centuries until the Qing dynasty’s corruption and ineptitude rendered China vulnerable to hostile foreigners (read, the West and Japan). These powers used their superior technology to defeat China in a series of wars, forced its leaders to sign unequal and exploitive treaties, and occupied Chinese territory.

This history presents Chairman Mao as the leader who brought the humiliation to an end on October 1, 1949, when he established of the People’s Republic of China and declared that the Chinese people had “stood up.” To this day, Chinese propaganda argues that only Chairman Mao and the CCP could unify China and give it the strength to resist the hostile foreign powers dedicated to splitting China and containing its rise. The Korean War is presented as an example of the CCP’s role in ending the “Century of Humiliation.”

The CCP continues to deploy the Korean War to garner patriotic sentiment, most notably in a steady stream of articles in Xinhua highlighting the return of “martyrs” remains to China from Korea. Although not as prominent as the Sino-Japanese Wars in popular memory, such narratives demonstrate the CCP’s commitment to the memory of the Korean War as an exemplar of national sacrifice and struggle.

Other publications use the conflict to project China’s identity as a moral defender of peace, a benevolent “older brother” to North Korea, and an anti-imperialist power with a record of victory against the West. A 2019 Xinhua article on the war argued that “the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army’s going abroad to fight was a righteous deed to protect peace and resist aggression.” Other articles in state media directly depict China as reluctantly forced into war by the United States and the Soviet Union.

China did not officially announce the number of soldiers killed in the Korean War (180,000) until 2010.

The Korean War also provides contemporary Chinese policymakers with ready historical analogies, and informs China’s approach towards the Korean peninsula today. Recent articles in Chinese state media idealize the culture of state secrecy in the war, warn of the importance of dialogue for international peace (perhaps an implicit reference to the contemporary North Korean nuclear crisis), and call for the implementation of the Korean War’s model of national defense modernization. Memories of the Korean War, and especially the tremendous losses endured by Chinese forces in the conflict, may also inform Beijing’s decisions to support North Korea in contemporary crises.

Even top leaders in China rely heavily on Korean War narratives. In 2010, then-Vice President Xi Jinping gave a speech that presented the conflict as the natural culmination of China’s triumphant retaliation against the imperialists who held the nation down during the Century of Humiliation. He also offered a compelling underdog narrative of a still impoverished country overcoming the wealthiest power on earth:

Loving peace is an excellent tradition of the Chinese people. Since modern times, the Chinese people, who have had their fill of the hardships caused by the imperialist great powers’ aggression and devastation, understand even more deeply the barbarity of aggressive wars and the preciousness of safeguarding peace.

Xi’s speech also lays out the continued importance of the Korean peninsula to Chinese security, drawing a straight line from China’s intervention in 1950 to its present policy:

The Korean peninsula is linked to China’s mountains and rivers, and safeguarding peace and stability on the Korean peninsula, and in Northeast Asia generally, relates to world peace and stability. China’s basic position and policy stance on this issue is consistent.

Regardless of what some revisionist Chinese academics argue, and despite internal frustration with the Kim regime over its nuclear weapons policy, Xi’s speech articulates a continuity between contemporary national interest in North Korea and the intervention of October 1950. Although Chinese policymakers, netizens, and scholars increasingly view North Korea as a troublesome liability, and see South Korea in a more positive light, the fundamental necessity of maintaining the Kim regime to provide a strategic buffer for China from the United States remains the guiding principle of China’s Korean policy.

Such calculations suggest that the Korean War experience will drive China’s leadership to continue to support North Korea and shy away from applying truly detrimental pressure. As scholar Wang Fei-ling put the case in Public Affairs in 1999: “Beijing clearly prefers the current political stability and the existing balance of power on the peninsula in the near future.” Within CCP policy-making circles, “traditionalist and conservative forces” still hold sway on Korean policy. China’s leaders remember the threat that justified its original intervention into the Korean Peninsula, and likely view it similarly today.

The Korean War narrative also shapes Beijing’s approach to U.S.-China relations, and illustrates its increasingly competitive characteristics. Anger towards the United States over the original Korean conflict remains present in Chinese politics, and history is used to reinforce Chinese assumptions of U.S. efforts to split and contain China, with Taiwan policy firmly in the foreground.

“Beijing clearly prefers the current political stability and the existing balance of power on the peninsula in the near future.”

Zhou Enlai’s initial five conditions to peacefully resolve the Korean War – issued prior to Chinese intervention in 1950 – clearly identify a perceived link between the American Seventh Fleet’s involvement in the Taiwan Strait. Contemporary Chinese narratives still connect the two issues directly. The author of a 2010 article in The People’s Daily for the 60th anniversary of the Korean War laid the blame for Taiwan’s continued separation at America’s feet, writing that “[China] had no choice but to indefinitely postpone its plans to liberate Taiwan.” These narratives frame America’s continued support for Taiwan as evidence of ongoing hostility, and justify the CCP’s inability to achieve unification.

Korea continues to contribute to a deepening U.S.-China competition. As analyst Scott Snyder argued in 2011, “China often looks at the Korean peninsula through the lens of Sino-U.S. strategic relations.” A planned THAAD missile deployment to South Korea in 2013, for instance, triggered widespread Chinese fears of an emerging American “containment” policy. This strong Chinese reaction to the deployment of missile defense systems on the peninsula provides a stark reminder of the ability of Korean tensions to impact wider U.S.-China relations. Given China’s views of the Korean War, instability in North Korea or a U.S.-led attempt to overthrow the Kim regime could significantly harm U.S.-China relations. Under this paradigm, the Korean peninsula will likely continue to constitute a hindrance to positive U.S.-China relations rather than a means for cooperation.

In this vein, China’s official discussions and remembrances of the Korean War may become a proxy for commentary about the state of contemporary U.S.-China relations. An intensification of official references to the Korean War in speeches and propaganda may therefore indicate Beijing’s recognition that relationship with Washington will be fundamentally hostile going forward. While China’s wars with Japan are highlighted much more strongly and consistently in its discourse, the elevation of Korean War narratives to a similar level of prominence will likely suggest efforts by Beijing to prepare the Chinese people for a long and painful period of confrontation with the United States.

Reading the Risks in History

The Korean War plays a far greater role in shaping and informing contemporary Chinese perceptions and strategies than it does in the West. The conflict contributes greatly to the CCP’s projection of China as a peace-loving nation, willing to directly confront foreign attempts to split and contain it, and powerful enough to succeed. By casting outgunned Chinese martyrs as patriots defending their country and sticking up for their Korean brethren against imperialist Americans, China’s leaders have constructed a myth that remains potent in sustaining the People’s Republic and the CCP.

.jpg)

Although some Chinese scholars have adopted more nuanced takes on the Korean War, or demonstrated increased annoyance with North Korea, Beijing’s definition of its fundamental national interests – ensuring stability in China’s Northeast and preventing the rise of a unified and American-supported Korea that might undermine the CCP – remains unchanged. China’s views on the Korean War may also explain its continued support for North Korea, and why it seems willing to risk so much over a country for which it has very little affinity.

Going forward, American policymakers should learn from past mistakes and understand how the conflict continues to animate the PRC’s approach to the Korean Peninsula. If the U.S. again fails to understand the goals and motivations of its adversary and rival, it is far more likely to repeat the same mistakes made in 1950.

Abraham Denmark is the Director of the Wilson Center’s Asia Program and a Senior Fellow in the Wilson Center’s Kissinger Institute on China and the United States.

Lucas Myers is a Program Associate with the Wilson Center’s Asia Program.

The views expressed are those of the authors alone, and are not those of the Wilson Center or of the U.S. Government.

(Cover photograph: Statue of People’s Volunteer Army Commander Peng Dehuai in Dandong, Liaoning. Ferox Seneca / Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)