Summer 2020

Scorch Marks

– Charles J. Hanley

Ghost Flames tells the story of the Korean War through indelible vignettes from participants.

Charles J. Hanley is one of our most accomplished American foreign correspondents, having reported from some 100 countries in a four-decade career at the Associated Press. His reporting on the No Gun Ri massacre of South Korean refugees by the U.S. military won him a Pulitzer Prize and Polk Award, and yielded a 2001 book, The Bridge at No Gun Ri.

His new book, Ghost Flames, is a unique, character-driven narrative history of the Korean War. It tells the story of the war through the experiences of 20 people who lived through it – from a Chinese general and an American nun to a child refugee and a U.S. Marine hero. The book offers an unflinching, truthful account of the Korean War’s dark underside, relaying little-known horrors – some of which the author helped bring to light as a journalist.

Ghost Flames will be published in August by PublicAffairs. But The Wilson Quarterly is pleased to offer readers a first look into this vivid new history. Our excerpts open with the North Korean invasion, and the experiences that day of a northern refugee girl in Seoul, and of a communist party functionary in Hungnam, North Korea.

SUNDAY, JUNE 25, 1950

In Seoul, ten-year-old Chang Sang awakens to war.

“Sang-iyah. Wake up.” The urgent whispers stir Sang from sleep. “Sang-iyah. Something is happening.”

Rubbing her eyes open, she sees the white beard and the handsome tanned face of Grandfather Kim. The Bible says God made man in his own image. This is how God looks, the girl likes to think.

.jpg)

This morning the old man seems worried. An uprooted farmer lost in the teeming city, Grandfather Kim knows this clever grandchild can discover what’s behind the commotion in the streets outside. At age ten, Chang Sang is the oldest and brightest of a half-dozen cousins, refugee children from the North, crammed into a little house in old Seoul. Obedient, curious, she quickly dons her white cotton top and skirt. She hurries out into the gray morning, trailed by a couple of little cousins, leaving a roomful of others asleep. It’s barely past dawn, the summer sun rising pale beyond low clouds. The feel of approaching rain is in the air. For so early on a Sunday, the streets are strangely active, people rushing here and there, or standing talking in pairs or small groups. The girl, tall for her age, and confident, darts from group to group, listening, picking up the news. She hurries back home, where the adults are returning from church, and announces to Grandfather and any who will hear:

North Korea is attacking South Korea. North Korean soldiers are coming to Myari, coming to Seoul.

The child’s words send a chill through the Kim household of northern-born Christians, one extended family among tens of thousands of people who have poured south in recent years, a human tide driven by social upheaval, fleeing the rise of communism in the northern half of a poor, backward land.

For so early on a Sunday, the streets are strangely active, people rushing here and there, or standing talking in pairs or small groups.

Someone turns on Uncle’s radio. All sounds normal until, at 7:00 a.m., Korean Broadcasting breaks in to report the attack. “There is little cause for concern,” it reassures listeners. “The 100,000-strong Republic of Korea armed forces are sound and intact.”

But beyond Seoul’s sprawl of mud-walled houses and tile roofs, of squat office buildings and antique temples, somewhere north of the two-thousand-foot-high mountains ringing the centuries-old capital, the South Korean army is falling to pieces in the thunder and lightning of artillery and heavy tanks pushing south, in drizzle and fog, through the valleys that point toward Seoul.

As the city’s 1.5 million people awaken, almost one-third of them refugee northerners, word of the sudden attack is alarming, but hardly a surprise.

In the five years since World War II’s end, when the U.S. and Soviet victors divided this former Japanese colony into separate occupation zones, the two halves have followed divergent paths, communist and capitalist, under their Russian and American mentors, each forming a government claiming sovereignty over the entire five-hundred-mile Korean peninsula. And their newly organized armies have clashed repeatedly at latitude 38 North, the dividing line, especially since American occupation troops left Korea a year ago, a few months after the Soviet army withdrew from bases in the North.

On this Sunday, as news and rumors mount hour by hour about the fighting at the 38th Parallel, just fifty miles to the north, the people of Seoul hope this, too, is another border skirmish, soon to end.

In North Korea, revolutionary Ri In-mo wonders, “Has the time finally come?”

“In-mo! In-mo!” His mother’s voice startles the exhausted Ri In-mo awake. “Listen to the news. It’s war!”

The young man collapsed in sleep just before dawn this Sunday morning. He now looks up from his mat. Beside his mother stands his young wife, arms wrapped tightly around their slumbering two-year-old girl. All fall silent and listen. The radio announcer repeats the news: the southern Syngman Rhee puppet clique, tool of American imperialists, has attacked North Korea from across the 38th Parallel.

.jpg)

Ri sits, shaking off his deep sleep, collecting his thoughts.

As propaganda chief for the communist Korean Workers’ Party in Hungnam, a port city on North Korea’s east coast, he spent the previous day in meetings at the local KWP headquarters. He is studying the new three-year economic plan promulgated from Pyongyang, the capital, in order to develop ways to promote it to the people.

Returning past midnight to their home in nearby Honam-dong, he found his mother, Kye-sun, and wife, Sun-im, waiting up for him. They talked into the small hours, Ri patiently explaining the visionary ideas of the great General Kim Il-sung, North Korea’s leader, a vision of a better future for poor Koreans like them. Their daughter, Hyun-ok, would be five years old at the end of the three-year plan, his wife remarked.

“Then we should buy a tricycle for her,” said the grandmother.

Her lighthearted words struck Ri, remembering how she regretted always that she could never buy her boy the playthings other children had. Their poverty deepened in 1917 when his father died from a mysterious disease, unable to pay for a doctor, seven months before In-mo was born, leaving her both a widow and a new mother at eighteen.

In their hometown of Phungsan, in Korea’s mountainous far north, she scratched out a bare living farming rocky soil and weaving hemp clothing at night. Finally, in desperation, she had to entrust the boy to her schoolteacher brother and his wife, a childless couple, to be brought up as their own.

At age thirteen, running an errand, In-mo witnessed Korean nationalist guerrillas assassinate the hated local Japanese police chief. One gunman beckoned to the boy and told him Koreans could be free and prosper only when they rid themselves of such colonial oppressors. In-mo thought of his mother’s struggles and of the plight of so many others, reduced to eating pine bark in the spring when stored food ran out. In-mo and school friends began visiting a well-known local political agitator, a man who told them about “capitalism, socialism, Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin,” he recalls.

In-mo became a boy revolutionary, breaking police station windows, collecting firewood for the needy, reading leftist anti-Japanese tracts to younger children in a secretive “Red Reading Society.” By age sixteen, he was in jail. After his release, the young Ri spent the coming years as a student and worker on the surface and as an activist underground seeking to subvert Japan’s colonial regime. In August 1945 he was in hiding in the mountains when jubilant friends came and told him Japan had surrendered and Korea was liberated.

He and local comrades formed Phungsan’s first cell of the Communist Party, soon renamed the Korean Workers’ Party. As the party’s postcolonial focus shifted to purging landlords and pro-Japan collaborators, he rose in the ranks. The tall, handsome In-mo Tongmu (Comrade In-mo) also attracted the attention of young party enthusiast Sun-im, ten years his junior. She pursued him, and they fell in love. During their courtship, his gifts to her included a bound history of the Soviet Communist Party.

In-mo became a boy revolutionary, breaking police station windows, collecting firewood for the needy, reading leftist anti-Japanese tracts to younger children in a secretive “Red Reading Society.”

By 1947 the growing Cold War hostility between the Americans and Soviets doomed to failure the two powers’ vague plans to reunify Korea. In 1948 both North and South declared themselves independent states, as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) in Pyongyang and the Republic of Korea (ROK) in Seoul. In that year, Ri was sent to join the Hungnam party committee, riding the eighty miles in the back of an open truck with his mother and his bride-to-be.

He now has put in two years of hard work with the Hungnam party, while the two Koreas have been locked in an increasingly explosive standoff, each threatening to take the other by force. On this Sunday morning, he wonders, “Has the time finally come?”

Ri In-mo, young Chang Sang and Ghost Flames’ other protagonists now embark on their own individual journeys through the upheaval and perils of war.

By August 1950, the North Koreans push U.S. and South Korean forces into a defensive quadrant in the southeast, the Pusan Perimeter. Then General MacArthur’s amphibious landing at Inchon, combined with a breakout from the perimeter, drives the weakened North Koreans back across the 38th Parallel. The counteroffensive rolls all the way to the Chinese border when, in late October, a huge Chinese army intervenes, sending the Americans and their allies into bloody, headlong retreat.

As the Chinese close in on Seoul, Hurh Won-moo, a teenager who hid beneath his home’s floorboards during the North Korean occupation of the city, makes a hazardous escape with his mother.

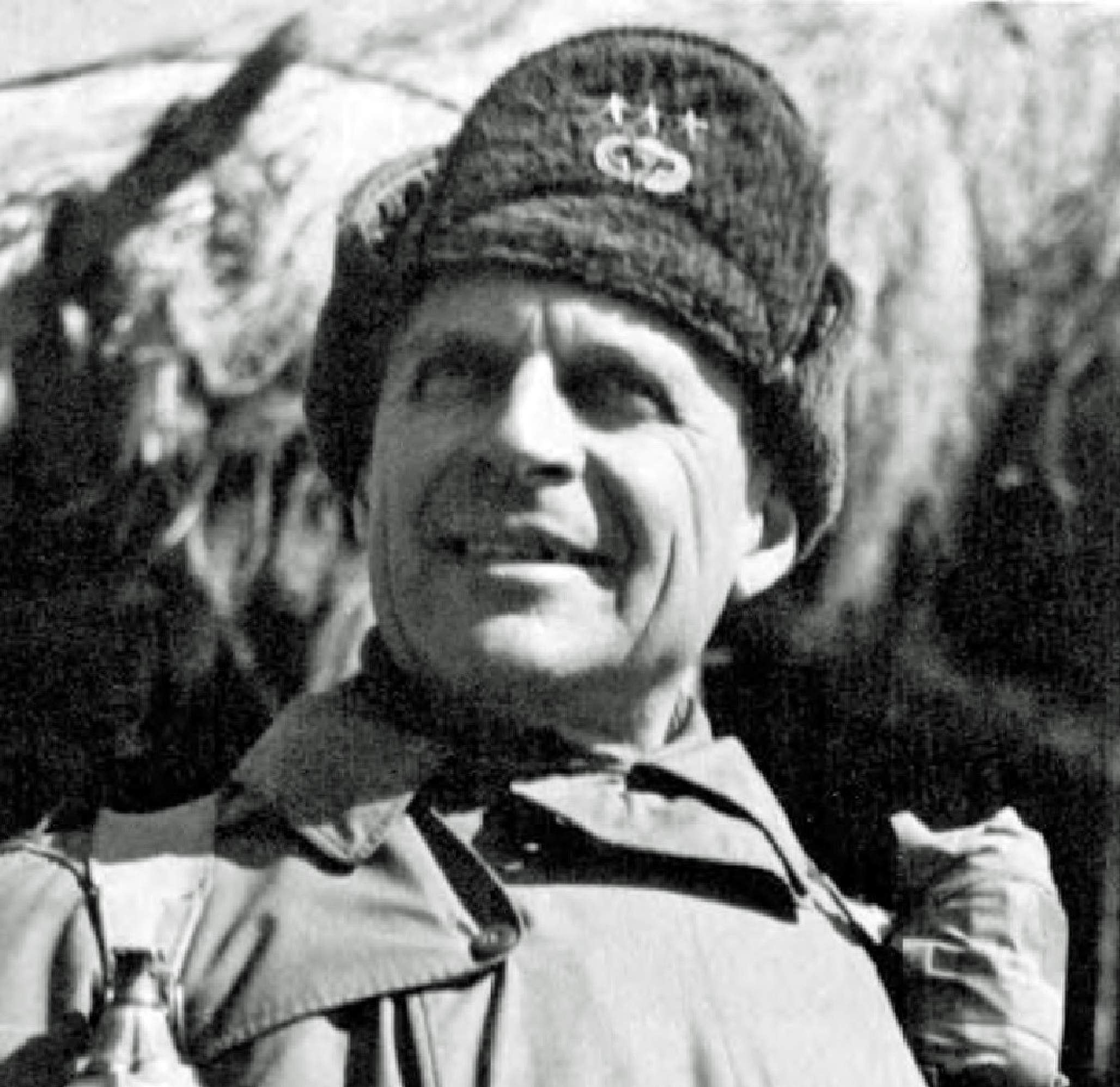

Lieutenant General Matthew B. Ridgway, just days into taking command of the U.S. Eighth Army, oversees a strategic withdrawal from the southern capital.

And Associated Press reporter Bill Shinn, a northern refugee in the south, sends final dispatches from a burning city.

WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 3, 1951

Hurh Won-moo flees with his mother across the frozen Han.

The only sound they hear is the crunch of snow beneath the feet of hundreds and thousands of silent people and the wind stinging their ruddy cheeks. Every step forward is terrifying. Just below the dark green ice, the frigid waters of the Han River still rush toward the sea. How thick is the ice? Will it hold?

Hurh Won-moo and his mother shuffle across the frozen Han, more than a half-mile wide, within an endless column of fearful people fleeing Seoul. The Americans’ makeshift bridges are filled with military traffic and will shortly be closed completely to civilians. All that’s left is the “ice road” of the river itself.

The Hurhs are among the last to leave in the unparalleled refugee exodus that began in mid-December. Word has spread that President Rhee and his cabinet abandoned the city this morning. At three in the morning, the Chinese attacked American rearguard positions just ten miles to the northwest.

The sad, strung-out multitudes push slowly over the ice, wrapped in layers of coats, in scarves and fur hats. Women balance bundles on their heads. Men lean forward with bags on their shoulders or with children on their back A-frames. Heavily laden oxen and oxcarts test the ice most dangerously, but it holds.

The eighteen-year-old Hurh, hefting a bulging duffel bag on his back, and his mother, carrying bundles of clothing, were not supposed to be leaving Seoul this way, on foot, uncertain of how they’ll get to their destination, Chonan, fifty miles to the south.

The ever-resourceful businesswoman had arranged for a man with a truck to transport the family and possessions last Friday to Chonan, where this miller’s daughter owns a disused rice mill she hopes to reopen someday. The family would sit out this latest phase of the war in the old mill workers’ quarters.

They waited all day Friday, and the trucker never appeared. In despair and furious—she had paid him a good sum in advance—they had to quickly find an alternative.

The next morning, cold and gray, the entire family went to Seoul Station, where civilians could mount the roofs of southbound freight trains evacuating military matériel. Hurh and his mother would stay behind, in hopes of finding the trucker and moving more belongings to Chonan. But his four siblings—three sisters aged six to nineteen and his nine-year- old brother—would be sent south with their maternal grandfather.

The scene at the station was chaotic, as families struggled to stay together and find space atop a train. The Hurhs saw a clear spot atop one car, and Mother quickly paid two young men to help lift all her charges aboard. With ropes, they tied their suitcases to an air vent, forming a square of luggage within which they hunkered down.

When the whistle blew and the train pulled away, Hurh and his mother could only watch and pray they would arrive safely at Chonan.

Back home, they did what they could to further close up the household and secure the family farm-machinery shop. They never located the truck driver.

Every step forward is terrifying. Just below the dark green ice, the frigid waters of the Han River still rush toward the sea. How thick is the ice? Will it hold?

Now, this morning, they finally reach the southern shore of the frozen Han, after what seemed to Hurh an eternity. Behind them, silent throngs still stream down from the city onto the icy white path toward the unknown. More than 2 million people, many from North Korea, have crossed the frozen river to safety.

Mother and son make their way through the snowy afternoon to Yongdongpo rail station, find a place atop a twenty-car military train, and hours later arrive in Chonan.

Lieutenant General Matthew B. Ridgway takes charge of the retreat.

In the dying light of the blustery afternoon, the American general stands above the Han River’s northern bank and watches the masses of refugees flow sorrowfully over the ice toward the far shore. Nearby, his army rolls south in retreat, endless columns of tanks and heavy guns, and of troops in trucks and on foot, filing over the pontoon bridges. Behind him, under the gray clouds, uncontrolled fires burn across Seoul.

Matt Ridgway is determined to make this retreat different from the rout Eighth Army experienced in December, when the Chinese struck in force. The army’s new commander has decided this time they will not run but will withdraw methodically, from defense line to defense line, keeping contact with the enemy, striking him, counterattacking and then pulling back, inflicting heavy casualties day by day, until Eighth Army is ready to strike back full scale.

He must husband his resources. After he ordered the withdrawal Monday to the initial “bridgehead” defense line north of Seoul, one of his corps commanders, Major General Frank Milburn, instructed his units to hold Seoul “at all costs.” Learning this, Ridgway countermanded the order, telling his old friend Milburn that such a stand-or-die command was demoralizing to the troops and a potential waste of manpower that will be needed later. Only he, the army commander, will ever make such a drastic demand on his soldiers, Ridgway said.

He has ordered today’s latest move south, leaving Seoul to the enemy once more, both because of the overwhelming power shown by the Chinese in their three-day-old offensive and because he fears they’ll soon be able to outflank him from the east, even advancing down the frozen river, cutting off the escape routes from Seoul.

Ridgway ordered the three pontoon bridges that were built by his engineers, replacing the Han’s single roadway-pedestrian bridge destroyed in June, to be closed to any but the military after 3:00 p.m. His orders are harsh: if fleeing civilians try to cross the floating bridges after that, the American MPs guarding the spans are to fire warning shots and then to fire into the crowds if necessary.

In buttoned-up field jacket and flap-eared pile cap, the Eighth Army commander has now stationed himself above the riverbank to observe the withdrawal over the main pontoon span, the trucks bumper to bumper, the armor and big guns widely spaced to not overburden the sagging bridge sections. He sees army engineers in rubber boats, armed with pike poles, grappling with the river ice to keep it from crushing or upending the floating roadway.

Well past twilight, satisfied the bulk of his exposed army is across the river, Ridgway returns to his room at the Seoul command post and packs his few things in a musette bag. Before departing in his jeep for the south riverbank, he and his orderly take a useless, worn-out pair of the general’s pajama bottoms, tack it to his office wall, and scrawl above it in large block letters: “To the Commanding General Chinese Communist Forces—with the compliments of the Commanding General Eighth Army.” Barely a week into his new command, Ridgway is already retreating, but he doesn’t feel defeated.

In a devastating parting shot, he has asked the U.S. Air Force to deliver a blow to Pyongyang, the northern capital, as he surrenders the southern capital. Sixty-three American B-29 bombers rain incendiary bombs on the city. Sixty more attack on Friday. “The entire city burned like a furnace for two whole days,” the North Korean radio reports.

THURSDAY, JANUARY 4, 1951

As Seoul burns, Bill Shinn commandeers a switchboard to send final dispatches.

The fires are most intense in central Seoul, where thick smoke fills the streets. Shadowy figures flit in and out of the glare of the spreading fires. Looters? Arsonists? The crackle of gunfire, unexplained, is heard now and then above the dull roar of the flames.

Near city hall, the Chosun Hotel stands untouched, silhouetted against buildings ablaze to its front and rear. Inside, Bill Shinn, who once helped oversee the Chosun as assistant manager, is manning the telephone switchboard, last link to the outside world for him and his fellow correspondents. The hotel’s Korean staff has fled. The reporters must get out the news of Seoul’s impending fall.

Shinn traveled to the front himself last week, to the ROK Army’s 1st Division, when he reported the defiant words of its general, Paik Sun-yup. He reported President Rhee’s dismissal of talk he was headed south. The situation “is quite secure,” the president said. Now, a week later, the bravado is gone.

Shinn has filed a brief, rueful article to the Associated Press in Tokyo about his adopted city’s fate at the center of a devastating war, a city about to change hands for the third time in just six months, and whose panicked residents still trudge southward across the frozen Han River in these final hours. “The deserted streets, the abandoned homes, the emptied office buildings—survivors of the first communist occupation—make observers feel the whole pathetic situation more acutely,” he writes.

Via the hotel switchboard, his AP colleagues report the Chinese offensive reached the outskirts of Seoul in the predawn hours this morning. Only small rear guards of U.S., British, and Australian troops remain in the city, steadily pulling back. The U.N. forces’ front line across the entire Korean peninsula is withdrawing southward. It’s time for the journalists to go.

Days ago, Shinn sent wife Sally and their two boys south to Taegu. Now his connections get him a seat in the official sedan of Seoul’s mayor, Kim Tae-sun. The others drive off in their assigned jeeps, rumbling over one of the pontoon bridges stretching across the Han.

In the 1st Cavalry Division, whose rearguard troops are among the last leaving Seoul, an order reads, “Effective immediately no refugees or other traffic, human or beast, will be permitted to cross Han River.”

From the opposite riverbank, correspondents witness wrenching scenes of desperation among the civilians fleeing the city and crossing the river ice.

Stumbling at times on the difficult footing, families struggle to stay together. Heavy loads are discarded. Oxen being led across, some pulling carts, are slipping and crashing to the ice, unable to get up, bellowing, likely with broken legs.

Then word comes down from somewhere, and American military police move out onto the ice, leveling their guns at the refugees, signaling for them to go back. They shoot the fallen oxen. They push the stunned people backward, step by step. Some cry out in disbelief and fear. But the soldiers’ menacing gestures finally force them to turn around, back to the northern shore.

This is soon followed by the whump, whump of mortars, lobbing shells onto the midriver ice, breaking it up. The U.S. military’s fear of infiltrators, its primal fear from the war’s first days, has taken hold again.

An instruction goes out from the U.S. Eighth Army command authorizing units to “stop all civilian traffic in any direction.” The means for doing it can be deadly. “Responsibility to place fire on them to include bombing rests with you,” the classified message says.

In the 1st Cavalry Division, whose rearguard troops are among the last leaving Seoul, an order reads, “Effective immediately no refugees or other traffic, human or beast, will be permitted to cross Han River.” Tragically, U.S. warplanes strafe and kill some thirty refugees on the ice, people turning back toward Seoul.

Bill Shinn and other correspondents face long hours of slow progress southward down roads jammed with military traffic and refugees, through Suwon and Taejon and finally to Taegu, where they again establish reporters’ bases.

Behind them, the last rear units pull back across the Han, military engineers blow up the remaining pontoon bridges linking Seoul to the rest of South Korea, and Chinese troops filter warily into the city. The war is entering a new chapter.

With Ridgway’s leadership and heavy Chinese losses, the Americans and their allies steadily retake land, including Seoul. By mid-1951, dueling offensives produce a stalemate around the 38th Parallel, and the two sides agree to cease-fire talks. The negotiations drag on for two years, as the conflict settles into a kind of trench warfare, a war of taking and losing hilltops, of small patrols and occasional large-scale, and largely inconclusive, offensives, and of devastating U.S. air bombardment of North Korea.

Agreement is finally reached and, on July 27, 1953, the armistice is signed. The next morning, Chinese army medic Chen Hsing-chiu, who entered the war as a 16-year-old eager to fight the “American devils,” is sleeping late.

TUESDAY, JULY 28, 1953

In the dark cave that has served as their latest battalion quarters on the central front, Chen Hsing-chiu stirs from sleep well past dawn. He retired earlier than the others last night, yet, as he looks around, he sees they’re all gone. He’s also the last of the medics to rise.

Was it unusually quiet overnight? He seems to have slept straight through, undisturbed by the usual thunder and vibration of enemy harassment shelling and bombing. But then, not all is quiet. In recent weeks, after twenty-eight months at the war front, Chen Hsing-chiu the weary soldier has begun hearing faint echoes of bombardment in his head, phantom sounds. Now that he’s awake, they begin again. The eighteen-year-old medic has prescribed sedatives for himself, but they do no good.

He hurriedly dresses, picks up his aid kit, and walks out into the daylight toward the battalion clinic. He sees a large truck headed south on the base’s rough road. It’s a shocking sight, a Chinese army vehicle exposed in daytime. He runs toward it, waving it down. He shouts up to the driver.

“Comrade, be careful! Enemy planes!”

The baffled driver stares at the oblivious young medic. “The war has ended!” he shouts back.

Chen is confused. “The war has ended?” he repeats quietly to himself. As the truck rolls past, he sees it’s loaded with wooden planks marked, “Demarcation Line.” Another truck follows with more markers.

What? It must be true, Chen realizes. He knew the Panmunjom talks had made progress, but his simple act of heading off to sleep early meant he missed last night’s message that guns would go silent at 10:00 p.m.

The baffled driver stares at the oblivious young medic. “The war has ended!” he shouts back.

The war Chen Hsing-chiu entered at age sixteen—the days and months and years of dread and boredom, of terror and blood, of friends made and friends martyred—had become life itself. And now it’s over.

“War is evil,” he writes in his diary. “It destroys forests, homes, villages. It kills and maims human beings. It is a threat to the survival of mankind on Earth.”

But this one, at least, has ended, he has survived, and he can go home a hero, one who helped humiliate the mighty U.S. imperialists.

“The entire Chinese people are proud. How can we not be, being victorious in this war? Rejoice! We are proud because we are Chinese.”

Ghost Flames will be published by PublicAffairs in August 2020. Pre-order a copy of the book here.

(Cover photograph: An aged Korean woman pauses in her search for salvageable materials in the ruins of Seoul, November 1950. National Archives and Records Administration)