Arctic Youth and the Anthropoceneby Michaela Stith

In the past 50 years, annual Arctic temperatures have increased more than three degrees Celcius on average. Permafrost thaw, glacier melt, sea ice reduction, seasonal shifts, and changes to biodiversity and migration are rapidly transforming life in the Arctic region. No one has witnessed these changes as intimately as Arctic residents, and many argue that the youth of the Arctic have the most at stake when addressing the resulting challenges.

In May 2021, the Polar Institute hosted The Arctic in 25 Years: First Annual International Youth Symposium at the Wilson Center. As the first-ever circumpolar forum of emerging leaders to be hosted in Washington, D.C., the Symposium gathered more than two dozen youth leaders from all eight Arctic countries and Indigenous peoples who live there to inform and influence potential Arctic policy for the next generation.

"Solving the climate crisis will require a whole-of-society effort in which youth play a critical role," said The Honorable Jim DeHart, U.S. Department of State Coordinator for the Arctic Region, at The Arctic in 25 Years.

Their lived experience and place-based Indigenous knowledge, passed down over thousands of years primarily through Indigenous languages, makes the viewpoints of Arctic Indigenous youth invaluable to climate change research and policy.

Hover to listen

“…as we look to the future, I think today's conference has exactly the right focus: a focus on youth, future generations, and Indigenous communities.”– The Honorable Jim DeHart, U.S. Department of State Coordinator for the Arctic Region

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) asserts the “tightly coupled relationship of northern local communities and their environment provide an opportunity to better understand climate change.” Over thousands of years, Arctic Indigenous peoples have developed unique, place-based knowledge systems that emphasize ways to relate to the living and non-living primarily through Indigenous languages.

Hover to listen

“…in the Unangam Tanangin/Aleutian Islands, [like] a lot of our life is built around the returns and the migrations of animals, salmon, and berries. And another major thing that we're seeing in the Aleutians is the lack of snow. Snow cover is really critical; it's critical for salmonberries and all of our berries. And one thing I want to note about that: those observations are multisensory in nature and they're embodied and they're witnessed and they're told and retold.

And this is one of the ways that our Indigenous knowledge systems are inherently interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary. You know I'm not just an artist, we are also scientists. We just might not be trained in the western language of science.”– Haliehana Stepetin (Unangax̂), Akutan, Alaska

Indigenous peoples' deep environmental competency is one reason why individuals and institutions engaged in environmental science and policy should adopt an Indigenous worldview. Despite an established recognition of Indigenous peoples' traditional knowledge as crucial to environmental policy, Indigenous knowledge systems have been largely excluded from decision-making across the Arctic region.

Hover to listen

“I think that international law has, since for a long time, recognized Indigenous peoples' special role in environmental sustainability. And we can see this through different frameworks in terms of looking at the Montreal Declaration, the Kyoto Protocol, and now even the Paris Climate Agreement, where copious mention of Indigenous peoples have been made, especially recognizing their traditional knowledge and the important role that they play in environmental sustainability.” – Larry Ibrahim Mohammed, Troms, Norway

Climate change is just one factor in the Anthropocene—the current age in which humans are the major determinant of the environment. Across the Arctic, youth who depend on the Arctic environment for their culture and sustenance highlight the interconnected challenges of industrial development, land rights, biodiversity loss, pollution, and human health. To tackle this suite of interconnected challenges effectively, they recommend holistic solutions rooted in redistribution of power and authentic relationship building.

Hover to listen

“Something that scientists look at and are realizing is ecosystem management is a way to manage. Let's say you want to protect salmon: You can't just protect salmon because salmon are connected to different watersheds and how the leaf litter goes into streams and are connected to how the stream is shaped so there is the right kind of habitat for their eggs or the right amount of oxygen in the water. The salmon are part of a larger ecosystem and a larger relationship, and so are people.

And so, community health, the land, and the environment are 100% part of community health. A community facing climate change can't have agency or ability to adapt if they're not given power over their land and resources. For scientists, I think it's important that instead of coming in and saying, ‘Oh, you need me as an expert, you need me,' changing that relationship to, ‘We need each other.'”– Jannelle Trowbridge, Nome, Alaska

Hover to listen

Although world governments have met more than 25 times to prevent global warming from exceeding 2 degrees Celsius, these negotiations have not translated into net emission reductions. Proposed solutions from these meetings, particularly carbon offsets and cap-and-trade schemes, have not been effective at reducing global emissions. At the same time, critics say these solutions effectively entrench colonial relationships between nations. With the Arctic warming three-to-four times faster than the rest of the world, young people from the North have been vocal about alternative solutions.

“Decolonization and revitalization of culture is very much tied to climate change, as industriality is a very huge factor to climate change. And the thing is also that industriality in Greenland has very much impacted our nature, our culture, and our way of living. We see changes every single year, every single day, on our animal patterns, diseases that they start to come, or changes in their behavior as well, or sea ice, which is the most important part of our hunting culture in the north of Greenland. Read More

As ice and glaciers melt, the Arctic becomes more accessible. Ship transits across the Northern Sea Route more than doubled between 2017 and 2020, primarily due to natural gas shipping on the Yamal Peninsula of Russia. Arctic youth articulate that such new developments should benefit Arctic communities. In Canada and other parts of the Arctic, revenue-sharing agreements are one tool used to redistribute corporate profits to Indigenous peoples.

The motion of sea ice on the Northern Sea Route from June 1st to October 10th 2021.

Hover to listen

“One of the most topical issues on the Russian agenda is the development of the Northern Sea Route because, in this case, we will have the annual supply for the Arctic Indigenous peoples. It is necessary to develop aviation on the country level, on the national level, and on the regional level. And as for the traditional livelihoods and hunting, it is a part of our life; it is the basis of our life. In this regard, I think we shouldn't think about the money, how much it will cost us, but those who are engaged in traditional livelihoods, they should get support from the state.”– Ivan Trofimov, Moscow, Russian Federation

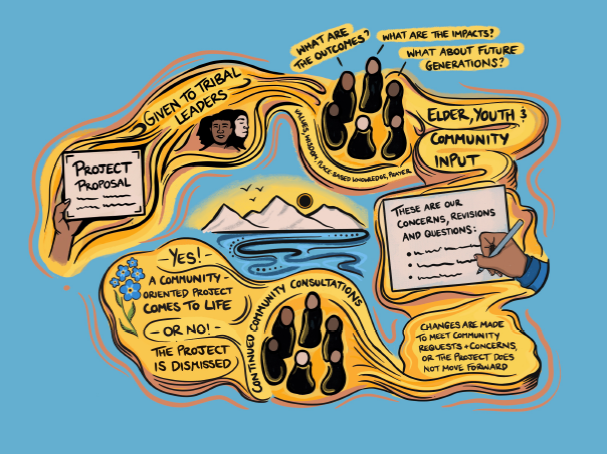

Free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) is one mechanism to engage Indigenous populations in discussions about policy and development. Recognized in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, FPIC enables Indigenous peoples to negotiate the conditions under which a project will be developed, implemented, monitored, and evaluated.

– Courtesy of Jessi Thornton, Native Movement

– Courtesy of Jessi Thornton, Native MovementWith the possibility of new transportation routes, Arctic states have built new plans for mines, oil and gas production, and other industrial developments. While many rural communities welcome economic development, Arctic youth stress that Indigenous leaders should have the right to decline any projects that may harm their communities' ways of life.

Hover to listen

“As we know, the interest to the Arctic has grown quite enormously due to the climate change and the rapidly melting Arctic. All the time there are new infrastructure plans, renewable energy projects, mines, etc. planned to our homeland that are threatening our way of life. We are all the time trying to adapt to the changing environment, to the climate change in addition to that at the same time these industrial developments are approaching.

So, we are attacked from all the ways. Our life depends on the land and the connection to the land and if there is no land there is no us. Our culture, livelihoods and way of life are connected with the land. In these cases these industrial developments that I mentioned before—the projects that could harm that connection and could harm our culture, we should have the right to say no to those plans.”– Enni Similä, Enontekio, Finland

And that means the Arctic's Indigenous youth must be engaged. To be effective, engagement must be meaningful, and authentic. Perspectives must be sought in the earliest stages, and updates regularly provided. And, they must be adequately resourced.

During the symposium, youth around the Arctic communicated many potential solutions to mitigate environmental degradation and adapt to “the New Arctic.” Commonly, they expressed ways to leverage power from institutions to communities so that research, policy, and decisions can be created by and for people on the political margins within their own borders. In one example, Norway created a law mandating every municipality in the country to have a youth council. Even so, novel engagement mechanisms such as these must be adequately funded and supported to be effective.

Hover to listen

“In 2019, the Parliament passed a law mandating every municipality to have a youth council here in Norway. Now, a few municipalities have had youth councils for up to 25 years, but a lot didn't even have one. This is a huge win for youth; we get a place to be represented in formal discussions. But there's a big difference between having a youth council just to follow the law, just on the paper, and having real engagement and participation in political processes. Some municipalities have a youth council that has no budget, does not have a secretariat or adult to help them, and they only have a meeting twice a year.

That's not involving youth. Some other municipalities have cracked the code: their youth council has a large enough budget, a good secretary, they get visits from bureaucrats and politicians, they are put in front of evidence and experts, they get schooling on how to argue and discuss, and involve not just elected youth representatives, but other youth too. By doing this, they bring key insights in local policies and have made a difference in their communities for the better.”– Johannes Lundvoll, Lyngen, Norway

In 25 years, the Arctic region may appear drastically different from today. The Arctic Ocean is expected to experience its first ice-free summers as early as 2035 and global fish stocks may be under threat of collapse by 2050. At The Arctic in 25 Years: First Annual International Youth Symposium, emerging leaders from across the circumpolar North challenged the audience to imagine new policy mechanisms and ways to adapt to this New Arctic. Their insights paint a picture of a just transition: a transition from extractive economies that are intimately tied with climate change to holistic, regenerative economies that support equity and human rights.

Hover to listen

“What is needed to transition an economy, meaning management of home, from one of extraction and exploitation to one of regeneration, is deep healing. But it also means returning to our Indigenous lifeways and our cultural and sociopolitical structures that enabled us to live in a regenerative economy for thousands and thousands of years.”– Ruth Miller, Anchorage, Alaska

About the author

Ms. Stith is a lifelong Alaskan passionate about the Arctic and environmental justice. She organizes events at the Polar Institute, manages the scholarly publication Polar Perspectives, and produces the blog column Polar Points. Ms. Stith handles communication including @PolarInstitute on Twitter and the New Security Beat column Navigating the Poles. In May 2021, Ms. Stith published her debut travel memoir set in Norway, Iceland and Alaska: Welp: Climate Change and Arctic Identities.

Ms. Stith is a lifelong Alaskan passionate about the Arctic and environmental justice. She organizes events at the Polar Institute, manages the scholarly publication Polar Perspectives, and produces the blog column Polar Points. Ms. Stith handles communication including @PolarInstitute on Twitter and the New Security Beat column Navigating the Poles. In May 2021, Ms. Stith published her debut travel memoir set in Norway, Iceland and Alaska: Welp: Climate Change and Arctic Identities.

Before joining the Wilson Center she lived and worked in Tromsø, Norway as a Hart Leadership Fellow and, later, as an Associate at the Arctic Council Indigenous Peoples' Secretariat. She provided assistance to Indigenous Peoples' organizations in their international policy work and supported events like the 6th Arctic Leaders' Summit. As a first generation college graduate from Duke University, Michaela earned Graduation with Distinction in Environmental Science & Policy for her thesis on Arctic cruise ship regulation.

Supplemental Medialicensed under Creative Commons

- Overhead glacier photo by Dylan Shaw

- Protest photo by @lnufoto on Instagram

- Icelandic drone footage by Wojciech Sulewski

- Lofoten polar light timelapse by goblivion

- MSTS Arctic Operations footage by Department of Defense (1958)

- Arctic Sea Ice Extent by NASA

- Sea Ice Movement on the Northern Sea Route in Summer 2021 by Great White Con

- Arctic Ice Is Thinning Twice as Fast as We Thought by Imagination