Spring 2021

The War Over Science

– Alex Long

Politics and distrust undermined public health responses in the U.S. and the UK. Why was the response of each nation's scientists so different?

It’s easy to look to the 2019 Johns Hopkins Global Health Security Index and cringe. The pandemic-torn U.S. and UK were ranked number one and number two for overall preparedness, yet both nations proved that no amount of planning, no amount of elite research institutions, and no amount of private industry excellence can compensate for volatile leadership.

The Index does have a "Political and Security Risk" indicator but clearly underestimated its impact. For instance, the U.S. ranked 59th out of 195 countries in that risk indicator, with a score of 75.0. But because its overall scores in other categories were so high, even if its Political and Security Risk score was adjusted to put the U.S. in last place, it would still be ranked first in overall preparedness.

Yet no pre-COVID-19 assessment of preparation could have anticipated U.S. leaders' willingness to ignore (or even flout) recommendations from scientists in a public health crisis and instead embrace the politics of perceived personal freedoms. And in the UK, science itself became the issue, as misconceptions of malpractice caused by a lack of transparency from policymakers led to a thirst for independent science. Unnecessary divisions were created in that nation’s public health community as well – to the detriment of public discourse.

Best practices in public health – and overall science policy – argue for two key elements: sufficient funding and independence from partisan infighting. These things are essential because good science aids in policy formulation (Science for Policy), yet science itself is a sector within government that needs regulation and oversight as well as funding (Policy for Science). Public trust requires that science (and government-funded science, especially) be seen as free of corrupting influence.

In conflicts between science and commerce (such as climate change, or Big Tobacco), corporations often attempt to erode trust through marketing campaigns, or by finding a champion within government to take up their cause.

But when a refutation of the science behind public health comes directly from those in power, the public is offered a nefarious binary: Believe the politician or the scientist. This binary then can split along party lines. False and true are boiled down to red and blue, to the detriment of the public.

So perhaps the Global Health Security Index is a site for questions, and not answers. The U.S. and the UK had the science, the policies, the plans, and the expertise to effectively respond, relatively speaking, to a pandemic. Why didn’t it matter? And, now, as both nations reap the bounty of scientific advances to leap ahead of the world in effective vaccinations, can we find our way again?

Sidelining the CDC

The Trump Administration’s adversarial relationship with facts was much remarked upon during its four years in office. But when it came to grappling with the COVID-19 pandemic, its readiness to accept and publicize untruths (such as the potential efficacy of hydroxychloroquine as a treatment) was accompanied by a willingness to demean and sideline federal entities charged with the task of dispassionately laying out public health guidelines and advice.

Inflicting a binary on U.S. society from the top down created parallel realities that led not only to paralyzing inaction, but also to conflicting public guidance that let COVID-19 run rampant throughout the nation months after the nature of the virus and its spread was understood.

Indeed, the White House Coronavirus Task Force went through several changes over its 11 months coordinating U.S. response.

Its first iteration was largely composed of political appointees, save for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Director, Dr. Anthony Fauci. Yet, in February, as cases started to rise, and the arguments that COVID-19 was a low risk to Americans disintegrated, former Vice President Mike Pence replaced Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar as the task force chair and took on the role of "COVID-19 Czar" full time, with Ambassador Dr. Deborah Birx serving as White House Coronavirus Response Coordinator.

The start of daily White House press briefings on March 16, 2020 promised a shift from downplaying COVID-19’s threat to the nation. But these hopes were soon frustrated by President Trump’s domination of daily conversations.

The U.S. and the UK had the science, the policies, the plans, and the expertise to effectively respond, relatively speaking, to a pandemic. Why didn’t it matter?

Yet the glare of the White House spotlight obscured what was perhaps the key development of the early days of U.S. response to COVID-19. The White House stifled the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) – one of the most revered and trusted agencies in the federal government – from the lead role it was expected to play in a public health crisis.

The administration had already contradicted CDC official Dr. Nancy Meissonier concerning her stark warning in late February that: "It's not so much of a question of if [an outbreak] will happen anymore, but rather more of a question of exactly when this will happen."

A literal sidelining of the CDC from the public eye followed – and at a moment when the agency arguably should have been front and center in response.

This isn’t what the pandemic planning and playbooks envisioned. Lawrence Gostin, the Faculty Director of the O'Neill Institute for National & Global Health Law at Georgetown University Law School says the optimal relationship between scientists and political leaders in a crisis "means having highly respected scientists tell the public honestly what they know and don't know. And it requires political leaders to support public health professionals and allow them center stage in health education."

Gostin’s view aligns with the CDC’s own vision of how it should work. In the 2014 edition of their Crisis and Emergency Risk Communications (CERC) manual, a designated Spokesperson is seen as "the most important role in responding to a crisis…Spokespersons don't just read a statement; they are the statement. If spokespersons don't fully understand the purpose behind the messages or recommendation, they will have difficulty assuming a stance of confidence and conveying believability and trust."

In essence, the initial decision to sideline the CDC and the continuing efforts to downgrade its status were the roots of a derailed U.S. response to COVID-19. And this harm was perpetuated further as the crisis grew, as reports emerged of the administration’s attempts to reopen society by distorting the agency’s guidance. Attempts to further undermine the CDC ranged from Facebook posts by assistant secretary for public affairs at HHS, Michael R. Caputo, to successful alterations of usually sacrosanct and scientifically rigorous Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports (MMWRs).

The vacuum in federal response filled up with falsehoods, misinformation, and worse – all aimed at promoting politics and not public health. Administration officials and the president called the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the disease it causes, COVID-19, “Wuhan Flu,” “China Virus,” and even “Kung Flu,” claiming without any publicly available evidence, that the virus's origins were more nefarious than a spill-over event. This rhetoric not only hampered global efforts to halt the pandemic but also created an uptick in anti-Asian hate and violence at home and abroad.

The CDC suffered immense reputational damage as well. A poll conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation found a precipitous drop in public trust in the CDC between April 2020 and September 2020. Confidence in the agency plummeted from 83 percent to 67 percent – and much of the damage tracked along party lines. Trust in the CDC dropped 30 percentage points for Republicans and only 12 points for Democrats. Republicans’ trust in Dr. Fauci also plunged in the same poll, from 77 percent in April to 48 percent in September – even as Democrats' trust in Dr. Fauci increased from 80 percent to 86 percent.

Especially among those who had long prepared a potential U.S. response to a global pandemic, the dismay at what happened to the CDC was palpable. "I was shocked that the White House so thoroughly undermined CDC.” Gostin observes, “and controlled virtually everything they did or said."

Leery of Lockdowns

White House rhetoric on so-called lockdowns – which also tracked with attitudes among many governors – also stoked partisan division over basic science. Early on, the available data and science on SARS-CoV-2 was sparse but growing. What was clear was that the disease could be spread through human contact – a process that social distancing and “lockdowns” would halt or at least slow.

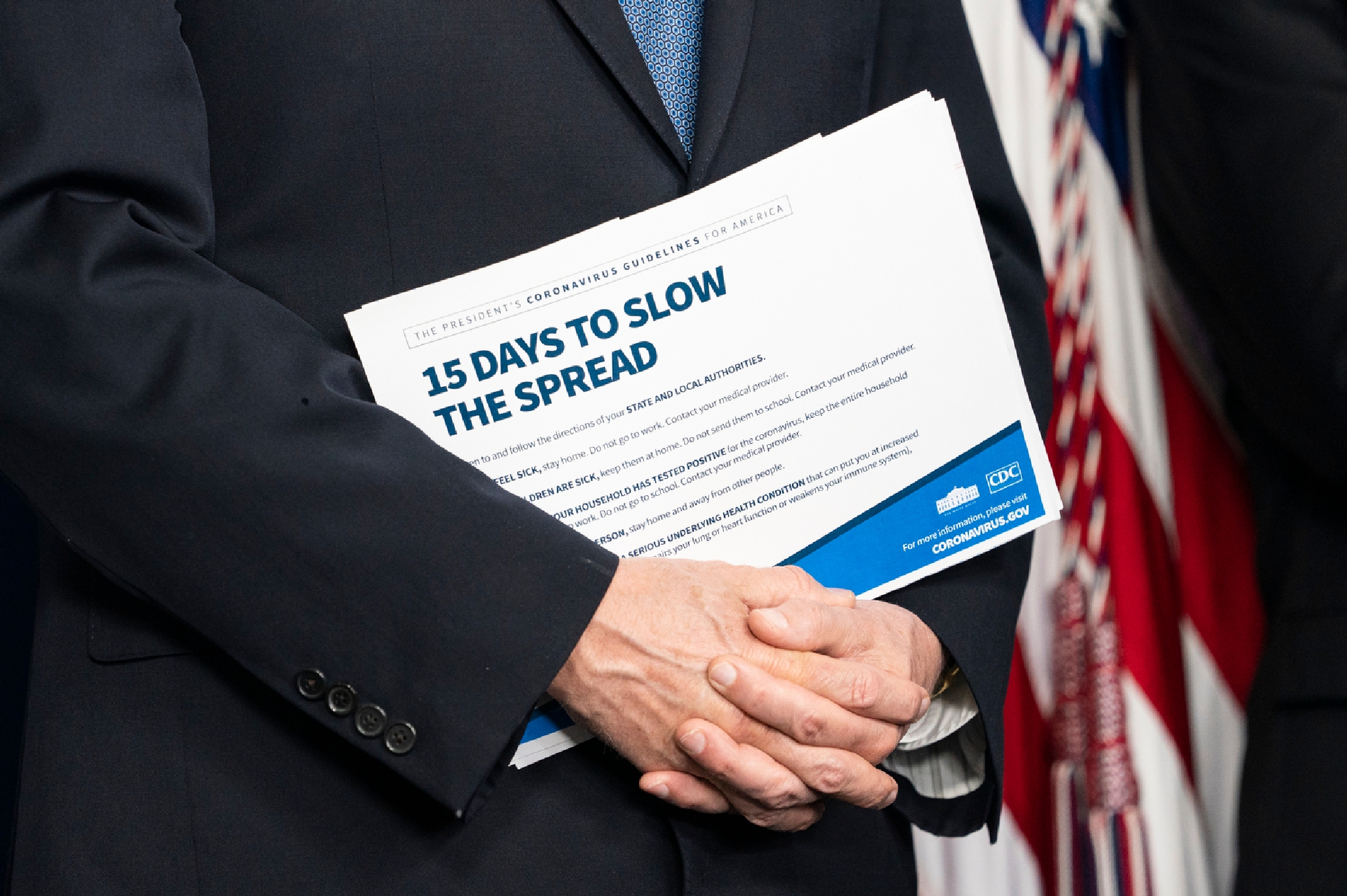

Because of this and observations from the lockdowns in the Hubei province of China, mitigation was implemented in the U.S., starting with a so-called “15 Days to Slow the Spread.”

As the 15 days was extended, the modeling science started to crystalize. Its conclusion? Strict mitigation measures would curb the rise in infections. The Imperial College London (ICL) analysis laid this out clearly in a foreboding and attention-grabbing report: Absence of any mitigation techniques would mean 2.2 million dead in the United States.

In early April, patience and trust in the process of mitigation were vital. Both were in short supply. Lags in testing, case counts, and data on the spread of the virus made it hard to officially prove to the American public that the lockdowns were working.

Later on, the expected data trickled in and supported what the public health leaders were reporting – the initial lockdowns worked. But it was too late for a success that required both proactive measures to obtain future results and executive leadership to inspire state and local governments to act in a coordinated and unified manner.

Indeed, events in the U.S. went in quite the opposite direction. The already-simmering politics of the issue boiled over on April 17, 2020, when President Trump sent out three separate tweets: "LIBERATE MINNESOTA!"; "LIBERATE MICHIGAN!"; and "LIBERATE VIRGINIA, and save your great 2nd Amendment. It is under siege!"

In a recent interview on CNN, Dr. Fauci recalled the moment: "The thing that hit me like a punch to the chest was then, all of a sudden, he got up and says: 'Liberate Virginia, Liberate Michigan.' And I said to myself: 'Oh my goodness, what is going on here?…It shocked me because it was such a jolt to what we were trying to do."

Protests erupted at some statehouses. Even worse, from a public health perspective, was that one by one, states began to come out of their lockdowns faster than they should have in the phased process offered by the Coronavirus Task Force.

In early May 2020, some governors reopened states even as they faced rising case counts confirmed by increases in positive test results. Georgia’s governor, Brian Kemp, announced his state’s reopening loosening restrictions on places like salons and gyms as early as April 24, without the data or trends to support his actions. Tennessee fell into line on April 30, followed by Florida on May 4.

This error in judgment was borne out by data. In the states that reopened before they met scientifically-backed guidelines, cases rose – sometimes to new and record-breaking peaks.

Dr. Angela Rasmussen, a virologist affiliated with Georgetown's Center for Global Health Science and Security, observes that: "This all started with the rapid reopening after that ‘15 Days to Beat the Virus’… I agree that we could have done a lot better if we had just come out of that more gradually and with the appropriate public health precautions in place."

The damage in politicizing effective non-pharmaceutical intervention was significant, Dr. Rasmussen adds. "One of the most harmful things hands down in this pandemic,” she says, “[was] the politicization of masks and taking precautions to avoid transmission... [M]asks were being adopted by a lot of Democrats. And, so, it became a very easy issue to politicize. And it's still a problem."

The politics cut both ways, as the pandemic wore on, and wearing a mask or not wearing one became a signal of partisan allegiances. (There were even Dr. Fauci bobbleheads, and masks with messages like #Science.) Past any assessment of the public health consequences, the fact that the nation’s battle against COVID-19 split along a red/blue divide signals a failure in response.

Rejecting SAGE Advice

The UK's extremely popular NHS healthcare system and its institutionalized support of independent scientists meant that it should have been better prepared to handle a pandemic in a unified fashion. But Great Britain’s similarly bleak track record during this public health crisis also had roots in polarizing politics.

Boris Johnson’s ascent to power in the wake of a contentious battle over Brexit was propelled by his ability to latch onto and connect with populist ideologies – especially amongst English voters. Johnson was known for making misleading claims about the UK's monetary contributions to the EU and other issues in the run-up to the Brexit referendum and beyond.

The polarizing nature of post-Brexit British politics has undoubtedly spilled over to its pandemic response. There is perhaps no clearer signal of this fact than how the role of a key pillar in response – a group of advisors dubbed SAGE (The Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies) – has become the site of contention.

SAGE is a group activated by the UK in times of crisis. There have been nine previous SAGE activations during catastrophes, including the Ebola outbreaks of 2014 and 2018, the Fukushima nuclear emergency in March 2011, the 2009 Swine flu, and other natural disasters.

The continuity provided by SAGE should give the UK a leg up on the more-diffused elements of U.S. response to such crises. SAGE participants are "leading lights in their representative fields from across the worlds of academia and practice. They do not operate under government instruction and expert participation changes for each meeting, based on the expertise needed to address the crisis the country is faced with."

SAGE’s authority resides in its intellectual firepower, and it is a key example of what Science for Policy should look like. Yet its limits are also explicit: "The government is not beholden to what SAGE says, and the evidence SAGE puts forward forms just one part of what the government considers before adopting new policies and interventions during an emergency." Policy should be informed by science, but leaders make the decisions.

In a confluence of ongoing political dissonance and a broadly-felt public health emergency, however, public trust was more greatly than ever rooted in a need for transparency.

Publicly, Boris Johnson was the face of the response. Similarly to Trump, he allowed officials and ministers in front of the cameras, but major policy decisions were announced by him. Rather than offering unfounded evidence or alternative facts, Johnson made a point to assure the public his actions were "guided by the science."

This assertion quickly became contentious. Which scientists? As SAGE’s public FAQ document notes: "Names of [SAGE] participants were not previously published to date in line with advice from the Centre for the Protection of National Infrastructure and following standard procedure for [Civil Contingencies Committee] meetings, to which SAGE gives advice." Additionally, their "black box" nature of giving guidance through private means to government officials proved too overly secretive in a moment in which distrust reigned.

SAGE’s opacity put science itself at issue. There was no way of knowing which scientists were guiding the government, and what influence they had on policy decisions. The issue of transparency boiled over in late April 2020 when two extremely polarizing government officials, Dominic Cummings (Johnson’s chief political advisor) and Ben Warner, (a data scientist known for his work on the Conservative party’s general election campaign), were revealed to have sat in on the secretive SAGE meetings in late March.

These two men’s ties to divisive issues like “Vote Leave” – as well as their status as partisan operatives – turned the secrecy surrounding SAGE into a public relations football. At a moment when UK citizens craved transparency and science-based policy, the scandal dealt a noticeable blow to trust.

The question of what science Johnson’s government was following undermined public trust in its response. It turned out to be one of the key elements in derailing the UK's response to the crisis.

Speaking Out for Science

In the United States, public debate and sharp media focus on pandemic response brought many controversies into the open. Yet the dissonance between science and politics continued.

Public health officials including Dr. Birx, HHS Assistant Secretary for Health Admiral Brett Giroir, and CDC Director Dr. Robert Redfield were all on the stage. (Eventually, Dr. Anthony Fauci was prevented from appearing.) Yet they proved unable or unwilling to assert expertise over statements made by President Trump that were not rooted in scientific evidence. Unfounded claims of effective treatments like convalescent plasma, hydroxychloroquine, and even bleach punctuated daily briefings.

While President Trump was fond of Twitter, a range of independent scientists found their voice to argue for science on that platform, and on a range of other media as well. Lack of pushback from agencies was what drove many of them into the fray.

Many of them also have become noted public figures in the process. Dr. Rasmussen had about 250 Twitter followers in February 2020. In April 2021, she had 211,400 followers. "I think one of the moments that did it for me,” she recalls, “was when [Dr. Birx] didn't correct President Trump about whether we could inject bleach."

Gostin understood Birx’s plight in that moment, but believes she made the wrong decision: “I know Deborah well, and she is an admired professional. But I don't have sympathy with this position. She had a choice either to speak truth to power or to resign. Going along with it, even if it is uncomfortable, would not have been my choice."

Independent U.S. scientists did not organize themselves into a single alternative task force. But they became a powerful and vocal presence, correcting falsehoods being publicized in the White House Press Briefing Room, as well as offering alternative research and support for best practices.

"One of the most harmful things hands down in this pandemic [was] the politicization of masks and taking precautions to avoid transmission..."

Infighting among scientific experts happens all the time and in all disciplines. These battles are fought in publications, at conferences, and on Twitter. But during a once-in-a-century pandemic, when scientific trust is so crucial, these independent scientists believed that the stakes were high enough that they had to speak. And they did so despite the dangers of the public seeing scientists contradict each other, or making seemingly-confusing assertions, or even creating questions about the supposed nonpartisan nature of science.

"I had little reservation about criticizing Trump's policies and false claims,” observes Gostin. “But I agonized about criticizing CDC officials and Task Force officials. I knew virtually all of them personally and respected them. But I felt they were not being strong and honest with the public and did not put science first. I realized they were under political pressure, but felt they should have stood up to it or resigned honorably."

Dr. Rasmussen notes that: "It's impossible to just stick to the science on this because science is inherently political. But when the science was intentionally politicized, I think that it's irresponsible for me to just sit back and say, 'Well, I have no opinion that I feel like sharing with people about whether or not to ingest bleach, or whether or not you should all be taking hydroxychloroquine.’ That would be irresponsible as somebody who works on viruses for the sake of improving public health."

An Independent Streak

It was different in Great Britain. The anxiety felt by scientists in the UK about controversies over the government’s claims to be "guided by science" led not to a decentralized media campaign, but to organized independent action.

These UK scientists founded an Independent SAGE (also known as Indie SAGE.). The new group worked to openly and transparently inform the public about their pandemic advice through the media and their personal platforms, independent of the government. Indie SAGE amassed a large following for delivering facts and administering guidance that the public could follow and the policymakers could potentially adopt.

Dr. Julian Huppert, Director of the Intellectual Forum at Jesus College at the University of Cambridge and a former Member of Parliament, noted that the transparency issues with SAGE opened the door for a new group.

"I think there's a real problem there,” he observes, “and a disrespect for those who were involved with SAGE. The narrative was these people work for the Tories. Therefore, they are Tories, and shouldn't be trusted.” But Huppert believes such reasoning bends the truth about the relationship between science and policy out of shape: “I think that would be like saying that Fauci must've been an ardent Trump supporter because he worked for Trump."

The emergence of Indie SAGE was a natural reaction to elusive accountability in the UK’s science guidance structure. But as Huppert points out, its creation also unfortunately institutionalized a distrust of SAGE. The resulting conflict has pitted well-meaning scientists against well-meaning scientists.

The dustup had other consequences as well. Eventually, SAGE members would speak out more publicly – and even release a membership list and meeting minutes. But the division between the two SAGEs remains, as does the British public’s uncertainty about who to trust as the nation tries to forge a path out of the pandemic.

Where Can We Go From Here?

In a perfect society, there would be no need for an Indie SAGE, or even a group of extremely active and media-savvy independent scientists, to step in and attempt to patch holes left by the government in the wake of a deadly pandemic.

Public health leaders should be positioned at the top of government response efforts, delivering good and bad news with humility and respect for the public they are informing. There should never be a fear of retribution on political lines, or a pressure to stay silent to stay in the room.

The embrace of anti-science sentiments and the politicization of public health has taken so much from us as societies – including our lives. Perhaps it is time to think seriously about what an independent group of scientists with diverse expertise could offer a country in times of crisis, as well as how they could be organized and regulated without sullying the objectivity that scientific guidance should seek.

Especially as seen in the U.S. in the COVID-19 crisis, there must be safeguards and referees to protect against political operatives taking the science and making that the debate, rather than debating which policies are being implemented. The UK example demonstrates that public health officials must be afforded transparency and given some agency over the policies enacted.

The lasting effects of weaponizing science for political gain don’t fade away after election day. Creating a secretive culture of policymaking during a crisis won’t inspire public trust in the process. A government-funded and scientific community-appointed reserve of experts is not out of the realm of possibility. But as pressing and potentially politicized issues such as vaccine passports and the spread of disinformation loom large, time lost waiting to address these issues is time wasted.

Alex Long is a Program Associate for the Science and Technology Innovation Program (STIP) at the Wilson Center, focusing on STIP’s Innovation Initiatives. Alex also is a Junior Policy Fellow with Cambridge University’s Centre for Science and Policy to research global health policy innovation.

Cover photograph: President Donald J. Trump, joined by White House Coronavirus Task Force Response Coordinator Deborah Birx, meets with Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson and Kansas Gov. Laura Kelly on May 20, 2020, in the Cabinet Room of the White House. (Official White House Photo by Shealah Craighead)