Spring 2021

A COVID Winter: New York City

– Richard Byrne

Conversations with Chris Hayes: Host of MSNBC's All In With Chris Hayes

The Wilson Quarterly spoke with a number of those involved in battling COVID-19 or covering its impact through a dark and challenging winter. Chris Hayes spoke with Richard Byrne.

In most presidential election years, prime time cable newscasts would be focused largely on the riveting horse race of American politics.

But a global pandemic changed all that. And few cable newscasts balanced coverage of public health and politics as well as All In with Chris Hayes – a broadcast now in its eighth year at 8 p.m. on MSNBC.

Chris Hayes’ background as a print reporter was evident in his insistence on bringing a wide and highly-diverse array of public health experts to talk about the ongoing catastrophe. And in a moment when expertise itself has been in a state of crisis, the host of All In brought the keen perspectives gained from writing Twilight of the Elites – one of the key chronicles of the breakdown of informed consensus governance in the United States.

Covering the pandemic night after night didn’t transform Hayes’ on-camera demeanor of affability and equability. But the gravity of the moment did exert new forces on both anchor and broadcast.

“I'm not a ranter and a table pounder,” he says. “And I don't think that's really my public persona, either. But this is the most horrifying, atrocious, abominable, moral abrogation by our government that I have seen in my adult life. And every day that goes by, I am horrified afresh. I feel an intense combination of shock, rage and angst – and urgency – about it every day. Because it just keeps going every day.”

On the cusp of the long COVID-19 winter, how would All In's host navigate the growing horror of pandemic and the toxicity of U.S. politics?

The Ghost Town (November 2020)

Every American has been compelled to reorganize their home and professional lives in this pandemic. Hayes is no exception.

“We've been back in Brooklyn for the last few months,” says Hayes, “because our two older kids are in public school, but they're all remote. We wanted to put them in the hybrid, but there's a pretty clear message sent by the school that like they need that space for parents whose kids absolutely need to be there…. So we're all in the house in Brooklyn. The kids are remote schooling. Kate [Hayes’ wife, Cardozo School of Law professor Kate Shaw] is teaching remotely. And I'm sitting in the living room with my laptop, and walking around the neighborhood doing my editorial calls.”

And what’s work like? Safety and minimalism reign – and Hayes even goes in late to the MSNBC studios at 30 Rockefeller Plaza to reduce his time in the building.

“I have to go to 30 Rock every day,” he says. “That has been fine and they've been really good. NBC's been really good. We have testing in the building. I get tested two or three times a week…It is really sparsely staffed. It's basically just me and a stage manager in a very large studio. There's one other person on my entire floor when I'm in the office. It's wild. It's like a ghost town there.”

Sometimes navigating family issues is the inspiration for the show. A powerful All In segment featuring Syra Madad and Dara Kass (who dispensed no-nonsense do’s and don’ts to help prevent holiday spread of COVID-19) that aired before Thanksgiving had its roots in his own family’s radical downsizing of its annual holiday meal.

In 2020, the customary large Hayes family feast became a much smaller (and much briefer) experience conducted under heat lamps. “It was a way that we can all be together,” he says, “and raise a glass to each other, and you give thanks in some version of ‘in person.’ That to me is a way to kind of square the circle a little bit.”

The practically-minded segment with Madad and Kass articulated the high stakes of family gatherings for viewers. “One of our producers was having literally this conversation with his family,” Hayes recalls. “And we thought we really should do this. I genuinely think we can help people, and maybe at the margins have some [public health] effect.”

“I'm not a ranter and a table pounder. And I don't think that's really my public persona, either. But this is the most horrifying, atrocious, abominable, moral abrogation by our government that I have seen in my adult life."

The urgency and intensity of a raging pandemic and a fiercely-disputed presidential election leave Hayes less time than one might expect for deeper reflections on big questions about COVID-19.

“These twin crises don't allow a lot of space for curiosity right now,” observes Hayes. “Right now, there are quite literally tens of thousands of people who are walking around, perfectly healthy and alive, who will be dead by January 20th. Tens of thousands of people out there, moving around the world right now, with no idea that just like that, the train is going to hit them. The bullet is going to find them. So I feel a very powerful responsibility to do everything we can about that.

“At the same time,” he continues, “there's a pretty sprawling – if, I guess, comfortingly ineffectual – effort to overthrow the democratically elected government and subvert the free and fair election in which the voters made their choice. Which also is a crisis. So there's a firefighter quality to the right now that’s a little incompatible with, like, ‘What questions are vexing me?’”

Possibility and Peril (December 2020)

There are still a few weeks before President Joseph Biden will be inaugurated. And the seemingly-unimaginable sight of a mob incited by the sitting President attacking the U.S. Capitol to stop the counting of Electoral College votes is still a week away. But the twin public health and political crises remain as much – if not more – on Hayes’ mind than they were a month ago.

Hayes sees the COVID-19 challenge boiling down to “administration of the vaccines – and everything else. I truly hope that we are able to quickly and efficiently vaccinate our way out of this. I don't know that that's a guarantee. In fact, I suspect it's not a given.”

The political situation, just days before it will simmer over in the nation’s capital, is also at the center of the anchor’s thoughts. “Our politics seem broken in a way that is more profound to me than I ever have seen,” says Hayes. “There's a lot of possibility in that brokenness, because I do think we're experiencing a total ideological implosion of, essentially, the neoliberal project from 1980 on…. And in the wake of that destruction, there's both possibility and peril. I just think our politics are deeply broken, and nothing’s clarified that as much as Trump's loss.”

The brokenness casts a pall on forecasts for the upcoming year. “At one level,” continues Hayes, “I have some optimism about the trajectory, in terms of vaccination, a return to normalcy, economic performance improving, people getting their livelihoods back, businesses hiring people, and people being able to put food on the table and all that stuff. But the underlying structural problems in American politics seem to me as bad as ever.”

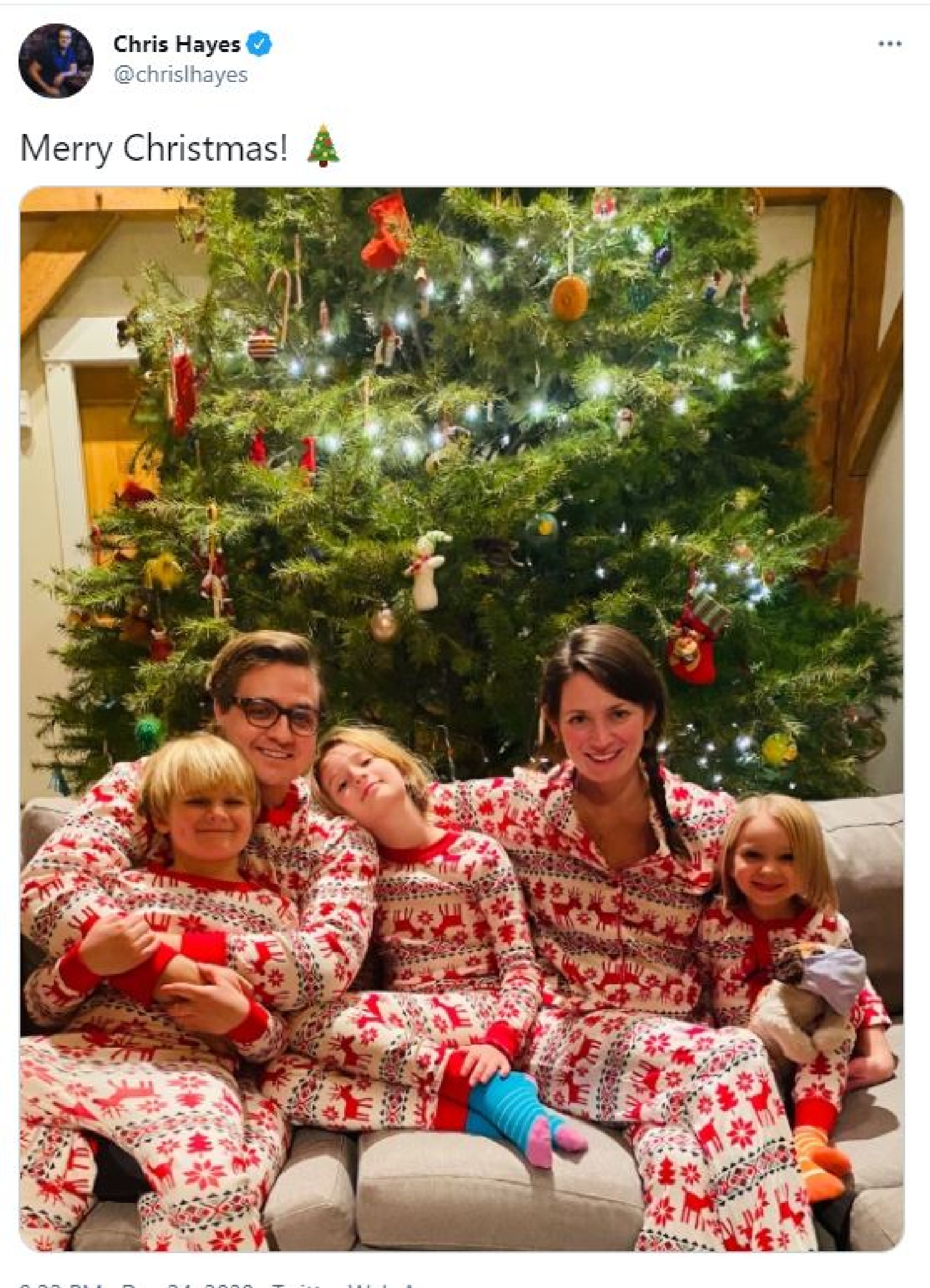

Hayes says Christmas was much like Thanksgiving – a scaled-down and socially-distanced gathering to elicit holiday spirit in a challenging moment. “We have a porch with two of those restaurant-grade propane space heaters…. And if you fire both those up, and one set of people stand underneath one and one set of people stand under the other eight feet away from each other, it's sort of tolerable to be outside. Even if it's super cold.”

Hayes says such gatherings, and Zoom calls, and even matching holiday pajamas are what the holidays of 2020 needed to be, however: “Everyone's trying to, you know, find replacements for the togetherness that we can't quite have exactly.”

In the Trump Administration’s final weeks, new details about its failed response to COVID-emerge on a daily basis. And the picture of the suffering and death in U.S. hospitals over the past year also is starting to become clearer – if only in bits.

“Right now, there are quite literally tens of thousands of people who are walking around, perfectly healthy and alive, who will be dead by January 20th."

“There's a familiarity and pattern to it all,” says Hayes. “We know what it looks like when a place has a bad outbreak. We hear all the stories: The freezer trucks, the morgues, the gurneys in the hallway, and medical staff working crazy shifts. So there's an extremely dark predictability to it.

“What continues to astound me,” he continues. “The thing that will never stop surprising me, is what we have – through, I think, evil abdication by [people] at the top – chosen to tolerate.”

Shining a Light (January 2021)

The host of All In with Chris Hayes often starts an interview with a guest by asking how they’re doing.

In late January, that same question elicits a blunt litany from Hayes himself.

“I don't know, man. I'm working out a lot. That’s good for my mental health. I'm finding this period tough. I think everyone does. I'm freaking sick of it. I miss my friends. I miss going out to dinner. I miss dropping my kids off at school. It's cold, so we can't socialize outside. And I have seniors in my life who are starting the vaccine and have also gotten COVID. So their health has been a source of anxiety and stress.”

Hayes reaches for a metaphor to put a bow on the thought: “It feels like the period when you're on a car trip, and you really have to go the bathroom, and the hardest part is the key in the door and walking from the parked car. When you're on the road, you put it out of mind. But as soon as the possibility of it being over tangibly enters your mind, it’s excruciating.”

The immediate change in tone and action on pandemic response from the Biden Administration is a welcome change – even if it will take weeks to move the needle on the horrible toll exacted by the winter surge in cases .

“We flipped over to the other side of the curve, which is encouraging,” says Hayes. “But, I mean, 4,000 people died yesterday. Recorded deaths. So being on the other side of the curve right now is: You’d rather be going down than going up.”

It seems impossible that there had been no formal national moment of mourning for victims of the COVID-19 pandemic until the evening of January 19, 2020 – when Biden and Vice President-elect Kamala Harris held a brief ceremony at the Lincoln Memorial on the night before Inauguration Day.

“I thought it was incredibly necessary,” says Hayes. “Very beautiful and very moving. I think it meant a lot to a lot of people. I talked to some of them, [since] I've been doing a little reporting on this [for a piece]. The total absence of acknowledgement or grief or memorialization. It's just so sick.”

"I'm freaking sick of it. I miss my friends. I miss going out to dinner. I miss dropping my kids off at school."

Hayes also points out that this silence has cut both ways. “The thing I keep coming back to,” he continues, “is there was a 41 year-old incoming Republican Congressman who died of COVID after he was elected. And there's a few statements here and there. ‘Oh, so sorry. So sad.' It's very upsetting.”

Calls for a commission into federal response to COVID-19 resonate with All In’s host, who has called for just such an investigation on the show.

“For me, there are two categories,” says Hayes. “There are lots of people that have screwed up and made mistakes in handling COVID. Republican. Democrat. Conservative. Liberal. Red state. Blue state. Utah. New York. New Jersey. It's a hard problem and there have been real mistakes. But the sociopathic way in which the Trump Administration dealt with it – the gaslighting and denial. From the beginning, it was like: ‘How will it affect me? “My poll numbers?’ And trying to basically make it go away as though it didn’t exist. There's just no comparison, you know. It's been more destructive in real terms. And it’s more morally pernicious.”

Hayes’ sense that vaccines are the central front in the U.S. war on COVID-19 is often reflected on All In. One late January segment featured public health workers in Josephine County, Oregon, who made sure that leftover vaccines in their possession did not go to waste by giving them to random motorists held up by an accident in a snow storm.

Hayes recalls that “the first thing I said on the editorial call was: ‘Can we… find them and see if they'll come on?’” He says that the segment was “a real-life dramatization of the difficulty of getting [vaccine supply, delivery, and demand] to line up.”

It was also a chance to shine a spotlight on the essential local workers who make huge vaccine rollouts and other public health measures work. “Part of it, too,” Hayes observes, “is ‘God bless you people for doing your job well.’

“I loved that segment so much,” he says. “I loved doing it. I loved it while I was watching it. I came home and showed [my wife]. It just gave me a good feeling inside.”

Optimism on Offer (February 2021)

As February ends, Hayes admits that “I have found pandemic winter brutal. I'm just really over it.”

Not that there aren’t bright spots. His parents are fully vaccinated now. “We have our health,” he says. “We have our family. The kids have been able to play in the snow a lot, which has actually been quite awesome.”

Looking forward to spring and his own vaccination even has Hayes ready to make a case for optimism – which he did recently in a segment on All In.

“I think a lot of people have had their hearts broken, and so often,” he says, “that it seems crazy to go out on a limb and be like: ‘No, actually, we are turning the corner.”

In particular, Hayes continues, “I really feel in some ways the conversation has undersold how amazing the vaccines are. And undersold the possibility that we really do suppress the thing.”

It’s not just being forthright about positive indicators. Optimism also can be an incentive to do the hard things that still need doing to crush the virus. “I think that it's important to retain hope,” he argues, “if that hope is borne out by the data.”

Hayes says that All In will mark the one-year anniversary of the pandemic in the United States with a live special from the Lincoln Memorial on March 11. Planning for the show has already begun.

"From the beginning, it was like: ‘How will it affect me? “My poll numbers?’ And trying to basically make it go away as though it didn’t exist."

“On one level, [COVID-19] is the most unifying story because there is not a single person in the country whom the pandemic has not touched,” he says. But experiences of the pandemic are also highly individual. “Some people have been out of work for a year and are going to food banks for the first time in their lives,” he observes. “Some people have had the busiest year of their lives.”

The show is soliciting viewers to submit video testimony about what the pandemic has meant to them. “What we're trying to do is sort of impossible in an hour,” he says. “To balance the universal experience with the kaleidoscope nature of the experience.”

Luck and Trust (March/April 2021)

March has already turned to April, and Hayes sees signs of renewal, and a desire to enjoy life, everywhere. Even in a bout of spring fever.

“I don't think anyone really wants to work right now,” he observes. “It was such a brutal year, and such a brutal winter. And now it's warm out and people are getting vaccinated, and it’s kind of hard to keep people’s minds focused on their labor.”

The sense of new possibilities created by increased vaccinations and falling fatalities is tempered by new variants, fierce regional outbreaks, and a sense that the world won’t be safe from COVID-19 until the technological benefits now being experienced in the United States are shared more widely.

“I'm more worried about the rest of the world, to be honest,” Hayes says. “Because they're not vaccinating at this pace. What's happening in Brazil is awful, and what's happening in India is really worrying.”

The seemingly haphazard nature of where the pandemic has struck the hardest effects leads Hayes to some uneasy thoughts. “There’s this fascinating mystery, which is that lots of places that we thought were going to get totally brutalized by [COVID-19] did not,” he observes.

Theories about why are legion. Weather. Societal experience with previous pandemic. Dozens of others. But Hayes wonders aloud if it actually “might be frickin’ luck. That you need a certain set of confluences to happen to basically get the fire roaring enough that it starts to take everything over. That's a very worrying thought.”

The March 11 episode of the show – hosted by Hayes at the Lincoln Memorial – was titled All In America: The Year We Meet Again. The segments that night included the story of a Mississippi woman who is relentlessly pursuing vaccination for her neighbors, as well as a crushingly beautiful account of an elderly married couple’s physical reunion after a year separated by lockdown.

Yet the show was also a bit of a high-wire act, as the All In team navigated a primetime address by President Biden that went longer than expected.

“We're all scrambling,” Hayes recalls. “The whole thrust and theme of show is about how it was both one pandemic and 300 million pandemics. If you start cutting at the last second, the finely-calibrated representation is thrown off.”

The pace of that night’s episode of All In was breathless. But the breathlessness seemed natural, especially in a special that surveyed a catastrophe that has unleashed so much illness, death and uncertainty.

In Twilight of the Elites, Hayes tracked the precipitous decline of trust in the experts and elites who helped shape consensus in post- World War II America. He believes that COVID-19 has been even more of a test for public trust than the battles over climate change.

“It is a theme I’ve been wrestling with for more than the last decade,” he observes. “Fundamentally, knowledge is dependent on trust. A radically balkanizing trust environment, a polarizing trust environment, and widespread distrust is going to lead to the inability to reach broad social consensus on basic knowledge. And that is our epistemic conundrum.”

Hayes says that “I'm a little out of theoretical ideas about how to fix it at the macro level. I just try to do my best as a practitioner. I don't know how much that's worth it in the end. I think that we used our platform for the people that trusted us pretty responsibly in the beginning [of the pandemic]. And I'm glad we did.”

Richard Byrne is the Editor of The Wilson Quarterly.

Cover Photograph: Times Square. March 16, 2020. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)