Spring 2021

A COVID Winter: Florida

– David Glenn

Conversations with Riley Jones, MD: University of Florida Health Shands Hospital and MedGlobal

The Wilson Quarterly spoke with a number of those involved in battling COVID-19 or covering its impact through a dark and challenging winter. Dr. Riley Jones spoke with David Glenn.

In early 2020, as the SARS-CoV-2 virus gathered its energies, Riley Jones was working as a physician in a refugee camp outside Cúcuta, Colombia, along the Venezuelan border.

Jones is 37 years old, and he had arranged his life in a way that seemed ideal to him. Six months a year, he practices internal medicine at the University of Florida Health Shands Hospital, in Gainesville. For the balance of the year, he practices overseas in crisis settings with MedGlobal, a humanitarian organization founded by the physicians Zaher Sahloul and John Kahler in the aftermath of the Arab Spring.

In mid-March, however, Jones’s plans for 2020 fell apart. The State Department warned U.S. nationals in Colombia to take the next plane out of the country, or else risk being stuck there indefinitely. Meanwhile, Jones’s colleagues in Florida texted him: They were putting together a team of physicians to care for the hospital’s acute and ICU-overflow patients, and they wanted Jones to be in the core of it.

Jones sat down with his spouse Rachel, a public health analyst who also volunteers with MedGlobal. It wasn’t an easy choice, but they decided to go home to Florida. With their three-year-old daughter, they boarded one of the last flights out of Colombia before the pandemic shut the gates.

Fast forward. Not even 36 hours later, Jones was wearing a face shield, gown, and the same N95 mask he had used in Colombia, treating COVID-19 patients on one of the two Intermediate Medical Care units at the UF Hospital.

In the 14 months since, those two IMC units have occupied almost the whole of Jones’s life. With the exception of a short break after his second child was born, Jones has worked eighty- and ninety-hour weeks, treating almost nothing but COVID. As the pandemic has unfolded in Florida, Jones has drawn upon principles he’d learned overseas, practicing medicine in the shadow of war and natural disaster.

Some of these lessons were things he never thought he’d need to apply in the United States.

Solving the Puzzle (September 2020)

“At some point, you’ve just got to step back from the humanity of everything,” observes Jones.

Six months into his marathon on the COVID units, he has seen misery on every shift: Patients struggling to breathe on high-flow oxygen, hoping not to be sent to the ICU. A young, previously healthy athlete paralyzed on one side of his body because of a COVID-related stroke. An immunosuppressed patient who’d been extremely cautious but caught the virus anyway. (Her one slip, she believed, was that she’d stopped at a gas station without a mask, and the person at the next pump had a cough.)

As a witness to all this trauma, Jones focuses on COVID-19 as a puzzle to be solved. “When you look at it from a more cerebral perspective, it’s an incredibly challenging disease,” he says. “We see all kinds of multisystemic problems that you’d never expect to see.”

At the outset of the pandemic, Jones’s hospital reconfigured several units to maximize the number of critical-care beds it had available. These ICU beds would be reserved for the sickest patients – those who required mechanical ventilation.

Meanwhile, COVID patients who could be maintained without a ventilator would be managed on the intermediate-care units by Jones and his internal-medicine colleagues, sometimes on high flow nasal cannulas delivering up to 80 liters of 100 percent concentrated oxygen per minute. On many days, Jones’s team carried as many as 150 COVID patients. The work fell heavily on Jones’s group in part because UF made an early decision to have experienced attending physicians, and not residents, manage the care of COVID patients.

Six months into the pandemic, Jones remains startled by the power and capriciousness of COVID-19.

“Some of our patients linger for weeks on high-flow oxygen,” Jones says. “We call them our rocks. But other people crash within a few hours after they’re admitted. I had one patient not long ago who had normal respirations and normal oxygenation at 5 a.m., and by 8 a.m., everything had gone wrong: Kussmaul respirations, crushing chest pain…. She suddenly had a myocardial infarction and went into diabetic ketoacidosis. And I can’t get her to the ICU, because there were no beds. That’s how fast COVID can hit people.”

Late summer was a relatively hopeful moment. Caseloads were lower than they’d been in the spring. Jones and his colleagues feel that they were starting to get a handle on optimal treatments for their COVID patients.

“When you look at it from a more cerebral perspective, it’s an incredibly challenging disease. We see all kinds of multisystemic problems that you’d never expect to see.”

Yet even in this interlude, ICU beds are sometimes scarce – and so are N95 masks. “I will use the same mask for about 14 service days,” he says. “I try to keep it on without touching it through the shift, so I’m pretty dry and pretty hungry by the end of the day. I just try to do everything I can to minimize the wear and tear on the elastic bands.”

Husbanding scarce resources is nothing new to Jones: He’s managed with much less in his medical work in places like refugee camps. Still, he is astonished that public-policy failures have placed his own hospital in this position six months into the pandemic.

“COVID has highlighted how quickly a rich country can become resource-poor,” he said. “Here we are in a major academic medical center, and we’re having to ration and scrounge around and make tough decisions about which staff get what PPE, [and] which patients get ventilators.… Declaring a public health emergency isn’t just for show. It changes how hospitals operate and how decisions are made, even on the individual patient level.”

Jones says two experiences put him on his present career trajectory. The first was a volunteer trip with an older friend in medical school to the Dominican Republic, near the border with Haiti. “On that trip, I realized this is how I wanted to spend my life,” he says. “Seeing people with illnesses that should have been prevented with just a trivial amount of money, but somehow weren’t – that’s something that I’ll never forget.”

The second experience was after graduating from medical school at the University of Louisville, when Jones earned a master’s degree in public health in post-conflict settings at King’s College London. He says this course of study most strongly shaped his approach to global medicine.

“That’s really where I found my niche,” he said. “It gave me a completely different set of contexts for thinking about health. My classmates were former child soldiers from the Sudan and Sierra Leone, public health professionals from the Congo, economists and humanitarians from every corner of the planet – it was just a fantastic group.”

Now, waist-deep in Florida’s COVID pandemic, Jones is watching the lessons gleaned from his King’s College experience about the fragility of institutions and the fragility of public trust play out in the richest country in the world.

Minds Made Up (October 2020)

The COVID-19 caseload at UF is creeping upward again. And with more than a million people dead worldwide, Jones finds himself losing patience with COVID skeptics.

“A couple of weeks ago I had one extremely sick patient who I was able to keep from going on a ventilator,” Jones said. “Which, it turns out, was good for her, because we didn’t really have space in the ICU. But when this lady’s family members visited, one of them consistently refused to wear a mask. She started asking me if Gilead [the manufacturer of remdesivir, a modestly effective antiviral medication] had an office here in the hospital. Apparently, she was onto some kind of conspiracy, this and that. And, honestly, at this point, I don’t even know how to respond respectfully to that kind of thing.”

Earlier in the pandemic, Jones would sometimes allow himself to be to engage in conversations about mask-wearing in the streets of Gainesville. Now Jones despairs of persuading anyone who isn’t already persuaded. “People have basically made up their minds,” he said. “People are just picking and choosing where they want to get their information from, as long as it’s cognitively satisfying.”

Alongside the rising wave of new infections, Jones is starting to see an increased number of post-COVID readmissions. These were not reinfections, but permanent lung damage inflicted by the initial disease. “I've got all these folks, of all different ages, who have developed pulmonary fibrosis,” he observes. “We're going to see a generation of people who will be walking around with oxygen tanks for the rest of their lives.”

On his days off, Jones joins online COVID-19 seminars with his MedGlobal colleagues in Bangladesh, Ecuador, and the Sudan. He shares practices from his hospital, but learns as least as much material as he’s taught: “Those sites have plenty of experience dealing with pandemics, even though they don’t have as many resources.”

A lesson from his tropical-medicine studies weighs on Jones’s mind. Dracunculiasis – also known as Guinea worm disease – occurs when people ingest water contaminated with a certain parasitic worm. “When the worm burrows out of your skin, you feel like your skin is on fire,” Jones said. “You get these excruciatingly painful ulcers, which then can be infected.”

“COVID has highlighted how quickly a rich country can become resource-poor. Here we are in a major academic medical center, and we’re having to ration and scrounge around and make tough decisions about which staff get what PPE, [and] which patients get ventilators.”

The disease was endemic in south Asia and sub-Saharan Africa as recently as the 1990s, but today it’s extremely rare. What solved the problem? “We never found any medicine that was even close to an effective treatment for Guinea worm,” says Jones. Instead, the disease was conquered by public health campaigns: Water systems were improved. Where that wasn’t possible, people were taught to drink through filtered straws and to bathe with buckets, rather than river water.

“Public health measures worked when no medicine would work,” he says. “We almost have this thing eradicated.”

Jones argues that a sizable segment of the U.S, public seems unable to apply these principles to a viral pandemic like COVID-19. It waits for magic bullets such as medications and vaccine, unwilling to make a sustained commitment to basic measures like masks, lockdowns, and physical distancing.

Amidst all the bad news, there is one positive trend: A reliable and steady supply of PPE. “We’re finally catching up,” Jones said. “We have an ample amount of N95 masks now. I’m still using mine for a week, just because that seems like the right thing to do – having seen where we were a month ago.”

No Heroes (December 2020)

Jones took three weeks of parental leave when his second child was born in mid-November. When he came back to work, the COVID caseload was still spiking, but his spirits were lighter.

“I'd just come off of paternity leave,” he said. “I'm hearing about the vaccine. I'm starting to get a little optimistic, and I'm feeling refreshed.”

That feeling of renewal didn’t last long. A week or so later, Jones lived through a crushing day.

“I had two patients who died at the same time, down to the minute,” he says. “And I’m telling one person that they can’t be officially pronounced dead yet, because I have to go pronounce someone else’s loved one dead first.” And later, down the hall, a third patient was rushed to the ICU because she’d coughed so hard that she ruptured her esophagus.

This day of tragedy was also memorable for a small farce. After nine months of meticulous caution, Jones finally suffered a high-risk exposure.

“I was eating lunch in an office that I’d started using because nobody else ever goes in there,” he said. “And one of our medical assistants came by to ask me a question. We're talking about the case, and then after a few minutes she gets a notification on her phone and she just very awkwardly walks away. She calls me ten minutes later and she's positive.”

Based on the size of the room and the fact that Jones was unmasked, the incident had to be considered high-risk. “The last thing I want to do is bring COVID home to my postpartum wife and infant,” he said. “We’d already set up a bed in the garage in case I ever had an exposure, and that’s what I started using.” But Jones notes this was still a step up from a borrowed camper he slept in without power throughout the Florida summer while his wife was pregnant.

“I’m telling one person that they can’t be officially pronounced dead yet, because I have to go pronounce someone else’s loved one dead first.”

Worse yet, this exposure came the day before Jones was scheduled to receive his first dose of vaccine. “I had a talk with my division chief about whether I should postpone,” he said. “The concern was that if I developed symptoms later in the week, we couldn’t be sure if they were from the vaccine or if they were signs of COVID.” In the end, Jones kept his appointment. He was one of the first clinicians at UF to receive the shot.

After nine months of pandemic, Jones says there have been tangible effects on his team. “We're sort of callous,” he continues. “We're a little sullen about it. We're all just sort of marching through. None of us” – he pauses in an uncomfortable moment of reflection – “we don't talk about being heroes, that's for sure.”

One of Jones’ greatest concerns is that Floridians might still be in the dark about just how bad the situation had become as the caseload rises toward Christmas. “In some sense, I think our official numbers are artificially low,” observes Jones.

He explains that patients aren’t counted in Florida’s official tally of hospitalized COVID-19 patients if they’d been hospitalized for so long that they are no longer considered infectious. “Years from now,” he said, “we’ll be sorting through the data, trying to figure out what the actual mortality level was from this disease.”

The Crater and the North (January 2021)

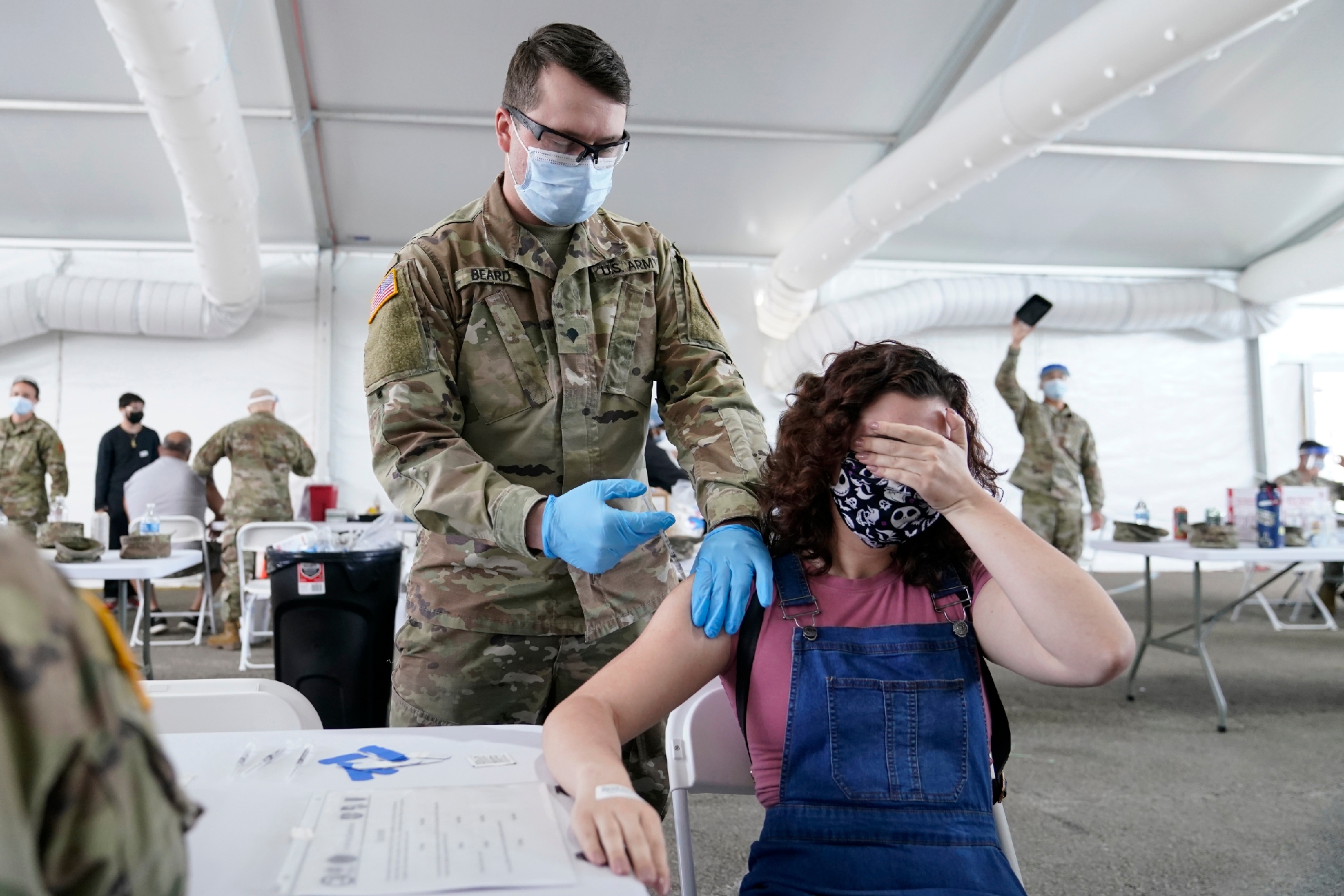

Jones has been devoting most of his days off to giving shots at a mass vaccination site at the University of Florida’s football stadium. He helped his aging in-laws, who live in a rural area outside Gainesville, negotiate the county’s sign-up system to get their own shots.

These activities have given Jones a new (and badly needed) sense of hope. On his IMC units, things are worse than ever.

“We’re absolutely at maximum capacity,” he said. “In the last week, we’ve had two married couples room together. At first we thought that was a humane thing to do – but after what I’ve seen, now I’m not so sure. If your spouse dies in front of you, and and you have to watch the brutality of the coding process, you can’t even mourn in a normal way.”

A high school classmate’s Facebook post also caught Jones’ attention amidst the ongoing crisis. This man had gotten COVID and sailed through the infection with next to no symptoms. “Now he’s posting,” says Jones, “as if he’s an authority, ‘Don’t worry about COVID. Go live your life.’ And, I’m sure it’s my availability bias, because I see the hardest cases, but I just couldn’t take that.”

Jones composed a long note to his classmate: “I said, I know some people go through COVID with no symptoms, and I’m glad that was the case for you. But let me tell you about my experience. Let me tell you about the mortality I’ve seen in just one day in one specific hospital room.”

At King’s College London, Jones read The Structure of Morale, a 1943 monograph by the psychiatrist John T. MacCurdy. “One of the things that book discussed was the impact of the Blitz, the Baedeker raids,” says Jones. “You had people in London who’d been incredibly traumatized. But then you had people up in the north of England, where bombs didn’t fall, saying, ‘Oh, it can’t have been that bad.’”

"Years from now, we’ll be sorting through the data, trying to figure out what the actual mortality level was from this disease.”

Jones resisted the temptation to write anything too cutting to his former classmate. “I could have said, ‘How would you feel if your wife came home with COVID and killed all the elderly members of your family?’ But that’s just incendiary. That’s not going to help anything. I just said: ‘Look. Let me tell you what I’ve seen. I’m in the crater of the detonation. And you’re in the north.’”

Keeping busy helps. Jones and his MedGlobal colleagues have started a new project: Helping hospitals in low-resource countries build large-scale oxygen concentrators, so they need not rely upon external vendors to supply oxygen tanks. “These things aren’t all that hard to build,” he observes. “But we’re trying to help people build them at a scale that could supply an entire hospital wing.”

Jones says that seeing doctors around the world pool their resources to send equipment to places like the Sudan is one of the most encouraging things he’d experienced during the pandemic: “I’m so impressed by my colleagues. It’s like they won’t allow themselves any more despair. They’re just going out and doing the work.”

Any Front We Can (February 2020)

The end of February has brought some relief. The COVID census on Jones’s unit is dropping. Patients admitted now tend to be younger, as Florida’s over-65 population is slowly vaccinated. Jones still works in a sea of illness and death, but he isn’t feeling overwhelmed.

“I’ve had more time to sit and reflect,” he said. “The thing about COVID is that it can affect so many organ systems that it really highlights the importance of all the bread-and-butter stuff you learn during residency. If you have that knowledge base, then, when something weird comes along, you can reason your way through it.”

“I’m so impressed by my colleagues. It’s like they won’t allow themselves any more despair. They’re just going out and doing the work.”

Resources remain scarce, however. “This even hurts our non-COVID patients,” Jones says. “This is Florida, and we’ve got our run-of-the-mill college students being silly. But if we want to test someone for gonorrhea or chlamydia, we can’t do the testing, because the lab has had to pull all the reagents to run COVID samples.”

Drawing on his experience overseas, Jones would like to teach his UF colleagues to manage another type of scarcity: a shortage (on the worst days) of time and personnel for running arterial blood gas (ABG) tests.

As the name suggests, these tests are drawn from arteries, not veins – and so they’re generally performed only by trained physicians or respiratory therapists. When those staff members are stretched thin, it can take a long time to get the tests done. “There was a time when I was doing well if I could get an ABG test done within six hours,” Jones says. “Ordinarily I could just go in and draw the test myself, but with COVID I’m putting out ten other fires.”

ABG tests are ordinarily required before a patient can be diagnosed with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). If a COVID patient develops ARDS, that is a strong signal that they’ll require intubation and ICU care - so ABG tests are important in triaging COVID patients. But Jones knows from his overseas work that ARDS can sometimes be reliably predicted without an ABG result, using less-invasive tests.

“That’s been well established for certain types of ARDS,” he says. “We just need to demonstrate that you can do it for COVID-associated ARDS.”

Jones and his internal-medicine colleagues still spend every spare day giving vaccinations at the football stadium. He says it is striking to see a mass-vaccination site function so well, when so many other parts of the U.S. public health apparatus had failed so badly. Jones’s spouse has also volunteered, signing people in and asking about allergies.

“We’re just trying to fight this thing on any front we can, much of it in small ways…but,” as Jones likes to say, “drop by drop, rivers are made.”

The Cat That Got Out of the Bag (March 2021)

As the pandemic enters its first full year ravaging the U.S., Jones feels less sanguine about the broader reach of the vaccination campaign. As in much of the rest of the country, Florida has significant disparities in vaccination rates, with low-income and Black neighborhoods receiving fewer shots.

“Some of that is vaccine hesitancy,” Jones said. “But I also think that the history of Tuskegee has been used in a nefarious way this time. People in power kind of shrug, and say, ‘Well, African Americans don’t want the vaccine because of the history of medical racism.' It’s almost been weaponized against these communities. Are we passively forgetting or malignly neglecting them?”

Drawing on his work in post-conflict settings, Jones tries to establish dialogue and trust in his own orbit. “If there are staff members at UF who’ve been reluctant to get the vaccine? Give me a donut budget and I’ll go talk to them in the break room,” Jones says. “It’s important to listen as much as to talk.”

Meanwhile, the local COVID caseload continues to drop, though Jones fears this welcome development is unlikely to last, as new variants of the virus begin to creep through the state: “I don’t even have the heart to think about it, but I’m sure we’re going to get another surge.”

Adding to the misery is the continuation of another trend: More post-COVID patients are coming through the door even as the numbers of patients admitted with initial infections drops. “We’re seeing post-COVID patients with neurological effects,” Jones said. “And some of those are severe. There’s also a lot of plain old depression and PTSD in people who were hospitalized with COVID, and I expect that those are going to be underdiagnosed.”

“I don’t even have the heart to think about it, but I’m sure we’re going to get another surge.”

These clinical puzzles are the only part of the pandemic Jones confesses that a part of him will miss when it finally ends. “These patients are so acutely ill and have so many different things going on,” he observes. “Every case has been a challenge, on an intellectual level. You really feel like you’re practicing at the top of your license.”

Jones wants to return to his work in Colombia this summer. “I’m itching to get back to my colleagues in the field,” he says. “I love my work at Florida, but the global health side – that’s really what I live for.”

Will his U.S. colleagues emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic with a deeper sense of the world’s interdependence and the fragility of public health? Jones hopes that they do.

“I don’t know why people have been so surprised by COVID,” he concludes. “Just in my lifetime, we’ve had pandemic after pandemic. There was HIV. There was SARS. There was Ebola and Zika…. TB is silently creeping back. This latest one just happened to be the one where the cat really got out of the bag. When we see public health crises around the world, we can’t just sit here and be passively malignant. It all comes around.”

David Glenn is an oncology nurse in Maryland. He has written for The Chronicle of Higher Education, Dissent, and The New York Times Book Review.

Cover Photograph: Medical personnel prepare to start a day of coronavirus testing in a parking lot outside of Raymond James Stadium in Tampa on March 25, 2020. (AP Photo/Chris O'Meara)