Summer 2020

Meatball Surgery

– John Strausbaugh

Hollywood didn’t dream up the Korean War’s most vivid U.S. cultural landmark. An irascible conservative doctor did.

In 1951, a young surgeon named Hiester Richard Hornberger was swept up in the so-called "doctor draft," enacted to address a shortage of medical professionals in the military, especially in Korea. That fall he was sent to Mobile Army Surgical Hospital 8055, one of seven such units, located just below the 38th Parallel. The conflict was settling into two years of grinding trench warfare along the 38th parallel, producing few tactical results, but much work for the doctors.

"The surgeons in the MASH hospitals," Hornberger wrote years later, "were exposed to extremes of hard work, leisure, tension, boredom, heat, cold, satisfaction and frustration that most of them had never faced before." The aggravated and exaggerated absence of consistency and routine "produced behavior in many of them that, superficially at least, seemed inconsistent with their earlier, civilian behavior patterns. A few flipped their lids, but most of them just raised hell, in a variety of ways and degrees." The tent where he and some other young doctors bunked and blew off steam earned the nickname “The Swamp.”

Sent home after eighteen months, Hornberger returned to Maine and started a private practice in the seacoast village of Broad Cove. Over the next few years the Korean conflict began to fade into the "forgotten war," but not for Dr. Hornberger. In 1956, he started working on a novel based on his Korean experiences.

He finished it in three years, then waited several more while his agent pitched it unsuccessfully to more than 15 publishers. Eventually, Dr. Hornberger engaged a professional collaborator, W. C. Heinz, a highly regarded sports journalist and former war correspondent to improve the novel’s prospects.

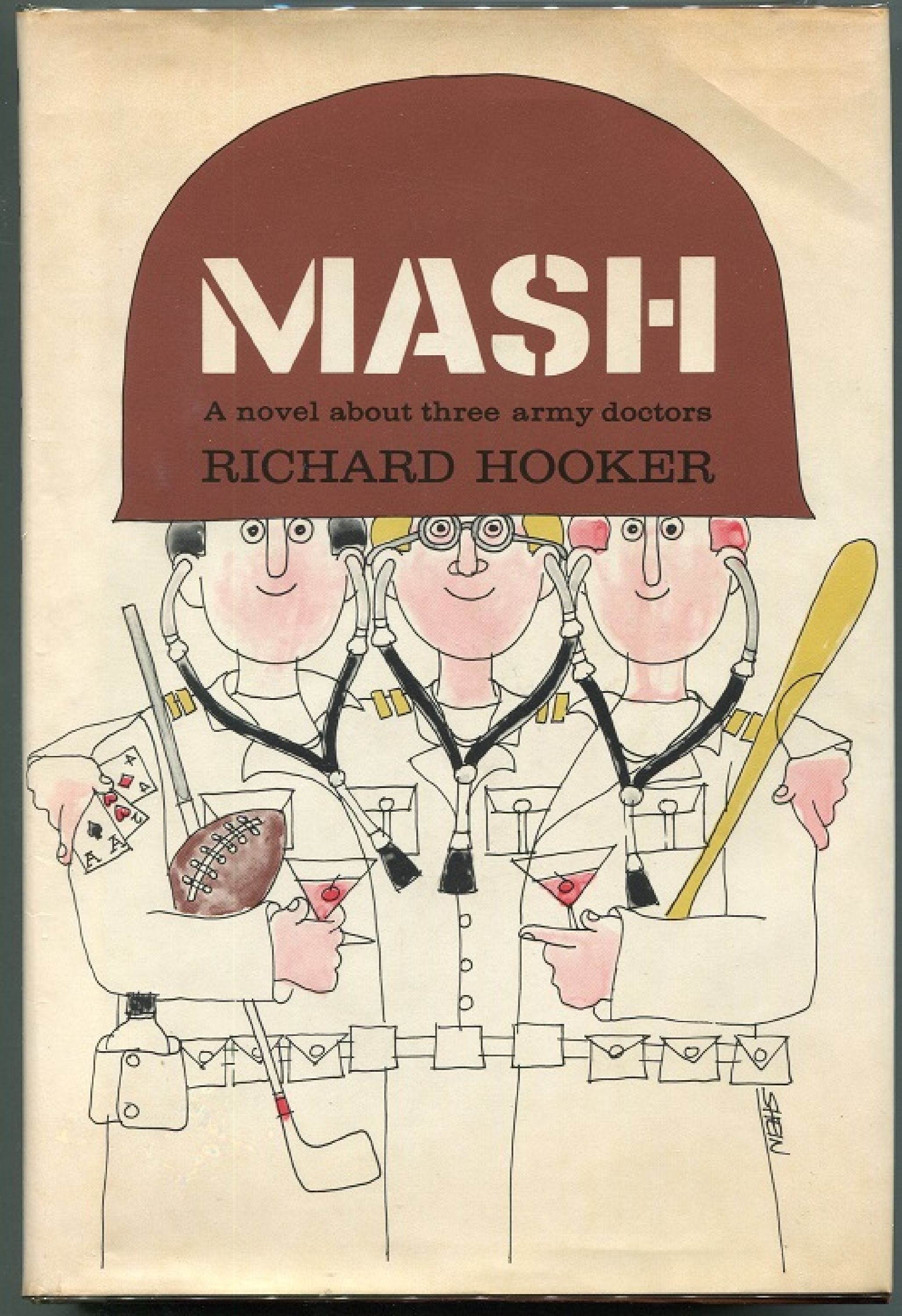

Their partnership resulted in success. The book was finally published in the fall of 1968 by William Morrow and Company, with Hornberger and Heinz using the nom de plume Richard Hooker. A paperback edition came out from Pocket Books the following year.

The book was a modest effort, more a loose collection of anecdotes than a novel with a coherent narrative arc. It earned a few small notices, then might well have been forgotten itself. But, as a single-paragraph review in the New York Times noted, the novel had one saving grace. "There is little continuity here but plenty of multicolored vignettes. More than enough, I'd say, for a shooting script or a series."

Indeed there was. Over the next few years, Dr. Hornberger's humble little novel was adapted first into one of the most successful films of 1970, and then, from 1972 into 1983, one of the most popular television series in broadcast history. The successes of the film and TV show in turn spurred the publication of no fewer than 14 sequels.

The title of Dr. Hornberger's novel was, if you haven't guessed, MASH.

Acting Out

Reading it half a century later, it's notable that for a book with such a legacy, MASH is surprisingly slight. It's no Catch-22 or The Good Soldier Švejk. There's no scathing denunciation of the madness of war, no merciless spoofing of inept military bureaucracy.

"I intended no messages in the book," Hornberger would later tell a reporter. "I am a conservative Republican. I don't hold with this anti-war nonsense." He simply wanted to tell some stories based on his time in Korea. Serious ones about doctors under pressure in the operating room, and humorous ones about doctors relieving the pressure with wacky hijinks outside of the OR. MASH is closer to the mild satires of army life in Mac Hyman's 1954 No Time for Sergeants (which itself spun off a long line of adaptations) or Bill Mauldin's Willie and Joe cartoons from World War II.

"There is little continuity here but plenty of multicolored vignettes. More than enough, I'd say, for a shooting script or a series."

Characters and other elements that became familiar to all Americans mostly through the long-running TV show are introduced. Hornberger modeled Hawkeye Pierce on himself, the 4077 on the 8055, Hawkeye's hometown of Crabapple Cove on Broad Cove, and The Swamp on, well, The Swamp. The rest of the characters – Trapper John, Duke, Hot Lips Houlihan, Frank Burns, et al. – were composites of people whom he served with.

Hornberger's attempts at humor dominate, both in tone and in length. A tedious and ultimately pointless shaggy dog about a football match between the 4077 and another MASH unit, for example, accounts for more than a tenth of the book. Any fan of the TV show would notice that Hornberger's versions of Hawkeye and his pals have much harder edges and are generally less likeable than their small screen counterparts. Their frat-boy antics are often boorish and bullying, mean and cruel, sexist and racist. (The one significant black character is nicknamed Spearchucker Jones.)

When the doctors of the 8055/4077 ridicule or rebel against military authority, it's simply because they know they are, in effect, the Big Men On Campus and can get away with it. They're never truly seditious. They're just acting out.

The book's strongest moments are Dr. Hornberger's memories of conducting "meatball surgery" in an OR that was like an assembly line of damaged youth when there was heavy fighting at the front. "And still they came,” he writes. “Bellies, chests, necks, arteries, arms, legs, eyes, testicles, kidneys, spinal cords, all shot to hell. Win or lose. Life and death."

These vignettes don't lead to political or moral statements. They're war-is-hell observations, their emotional impact in the simple way he tells them:

The six o’clock chopper, either morning or evening, was always unwelcome because the very fact that the pilot was risking the trip in half-daylight meant that the soldiers lying in the pods were seriously wounded. So twice each day, at dawn and at dusk, as six o’clock approached, everyone – surgeons, nurses, lab technicians, corpsmen, cooks and mostly Lt. Col. Henry Blake – would listen…

Gone Hollywood

Producer Ingo Preminger, Otto's brother, optioned the book for film, and hired Ring Lardner, Jr., to adapt it. An interesting choice, given that Lardner was a former member of the American Communist party who was jailed and blacklisted as one of the Hollywood Ten.

Robert Altman was said to be the 18th director whom Preminger approached with the project. He had directed dozens of episodes for various television series, but only a few small feature films, including the sci-fi Countdown and the psycho-thriller That Cold Day in the Park. Unknown to Preminger, Altman was beginning to fancy himself a Hollywood rebel, and used filming the film (now M*A*S*H, with asterisks) as a chance to prove it. He exaggerated the episodic nature of the novel (which he later said was "pretty terrible") to make a rambling, virtually plotless movie, and jettisoned much of Lardner's script for ad-libs and improv.

.jpg)

Lardner griped – until he won an Academy Award in 1970 for best adapted screenplay. Altman also amped up the book's mean-spirited sexism, as in the cruelly humiliating treatment of Hot Lips Houlihan in the film’s nearly unwatchable shower scene.

Altman made no attempt to have his actors look or act like it was the early 1950s; their long hair, hip speech and insouciant demeanor were all late-60s counterculture chic. He wanted audiences to think of the current Vietnam War, not the forgotten Korean one. In fact, the film's only references to Korea were added in by studio executives.

Altman exaggerated the episodic nature of the novel (which he later said was "pretty terrible") to make a rambling, virtually plotless movie, and jettisoned much of Lardner's script for ad-libs and improv.

Nervously released by those execs in March 1970, M*A*S*H startled them by becoming a tremendous hit with both critics and audiences. The antiwar, anti-authoritarian surliness was a perfect fit for the times. Made for under $4 million, it earned more than $80 million, making it the third highest grossing movie of 1970 (behind Love Story and Airport). It was nominated for five Oscars. It made stars not only of Donald Sutherland and Elliott Gould, but of Altman too. Even Hornberger liked it, despite its Commie pedigree and counterculture tendencies.

Given the smash success of the film, Morrow and Co. encouraged Hornberger to write a sequel. In MASH Goes to Maine, published in 1972, Hawkeye and his surgeon friends Trapper John and Duke muster out of the army and go to practice in Hawkeye's home state. Like the first novel, it's a loose-limbed gambol through variously implausible pranks and shenanigans. One gets the sense that whereas the foundation of the first book was Hornberger's memories, this one was more a retreat into his fantasies.

A Dose of PC

Maybe that's why MASH Goes to Maine feels so out of touch with the current events of 1972. It was a topsy-turvy year. Richard Nixon made his historic trip to China, got entangled in the Watergate scandal, and was handily reelected anyway. The war in Vietnam dragged on, and Jane Fonda made her infamous tour of the North. The Weather Underground exploded a small bomb inside the Pentagon, and George Wallace was shot. John Wojtowicz held up a bank in Brooklyn to pay for his lover's sex-change operation. Deep Throat introduced "porn chic."

Meanwhile, the original novel came to TV. The series was quite different from Hornberger's original conception. As played by the shaggy-haired, Groucho-imitating Alan Alda, Hawkeye had no hard edges, was never cruel, poked fun but never humiliated. At worst he was a smart aleck. After a few seasons he lost his wisecracking sidekick Trapper John (Duke was never in the series), who was replaced by an entirely new character, the relentlessly mild-mannered B. J. Hunnicutt. Over time, Alda's role expanded from starring to producing, co-writing, and sometimes directing, with the result that in its last several seasons, the show grew ever more liberal, feminist, antiwar and politically correct.

M*A*S*H, the series, was another grand success. Tens of millions of households tuned in every week for 11 years. It racked up 14 Emmys. The two-hour finale that aired in February 1983 had almost 106 million viewers, the largest audience for a TV program until it was edged out by Super Bowl XLIV 27 years later. It spun off two sequels, Trapper John, M.D., which enjoyed seven popular seasons (1979-1986), and the shorter-lived AfterMASH (1983-1985).

In his 2012 book, MASH FAQ, Dale Sherman reports that Pocket Books, seeing early on how popular the TV show was, asked Hornberger to write more sequels. He said he was too busy with his medical practice, but agreed to the hiring of a ghostwriter, as long as he had approval of the writer and any manuscript. After rejecting several candidates Pocket Books sent him as "longhaired liberals," he liked William E. Butterworth, a prolific writer of military and detective fiction, and a fellow Korean vet.

Butterworth dashed out MASH Goes to New Orleans in three weeks. He cranked out 11 more books by 1977 – MASH Goes to Paris, MASH Goes to Moscow, and to Hollywood, Las Vegas, and so on. These were all credited to Richard Hooker and William E. Butterworth, but in fact were entirely written by Butterworth.

Trampled Memories

Meanwhile the TV M*A*S*H rolled on, from Emmy to Emmy. If there was one person in America who did not like the show, it was Dr. Hornberger.

When he died in 1997 at the age of 73, his son William told the New York Times, ''He liked the movie because he thought it followed his original intent very closely. But my father was a political conservative, and he did not like the liberal tendencies that Alan Alda portrayed Hawkeye Pierce as having. My father didn't write an anti-war book. It was a humorous account of his work, with serious parts thrown in about the awful kind of work it was, and how difficult and challenging it was.''

Hornberger wrote one more MASH sequel on his own, MASH Mania, published in 1977. The whole book reads like a bitter refutation of the goody two-shoes Alda vehicle. Already by page 4, Hawkeye is lecturing the reader on why the use of the N-word and other ethnic slurs is not an automatic sign of bigotry. Four pages later, he chases Spearchucker Jones down a hospital hallway, cracking a whip. Further along, he and his pals brutally ridicule a rape counselor. "We understand you graduated summa cum laude from rape school," Spearchucker says to her. Trapper explains to her that Hawkeye is "planning to rape someone but he has no experience."

Hawkeye asks "just what does your counseling service provide? Like, who selects the victim, you or me? Like do I whack her around a little first…"

And so on. Even 40-odd years ago, it's unlikely that many readers took this as the rollicking, anti-PC fun Hornberger meant it to be. Like the humiliation of Hot Lips in Altman's film, it just is – and always was – mean, ugly and crass. But it's also impossible to imagine Alda's Hawkeye saying or doing any of these things, which must have been precisely Hornberger's point.

As the television show was coming to an end in 1983, Hornberger began appearing in interviews as the real Richard Hooker, and complaining. It was his last time in the limelight, and he came to bury M*A* S*H, not to praise it. He told Newsweek that the show "tramples on my memories." To UPI, he said: "If you're going to start a war, you might as well play to win. No one in their right mind would be pro-war, but I operated on a thousand or so wounded kids, and I know more about war than a bunch of undereducated actors who go around blithering those sanctimonious, self-righteous noises."

He went on, "My wife and I were in a hotel room in New Zealand one time and had the choice of watching The Dukes of Hazzard, M*A*S*H, or an educational program on the artificial insemination of cows. I chose to watch the cow show."

Reportedly Dr. Hornberger drafted another MASH sequel, about Trapper John being elected president of the United States. It was never published.

John Strausbaugh is an historiographer and journalist. His most recent books are Victory City: A History of New York and New Yorkers during World War II and City of Sedition: The History of New York City during the Civil War, which has been optioned for television.

(Cover photograph: The 8225th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital, Korea, in October 1951. National Archives and Records Administration)

(Video: National Archives and Records Administration)