Summer 2020

Bridges at Panmunjom

– Lt. Col. Sean Morrow

The former commander of the United Nations Command Security Battalion-Joint Security Area in Korea’s DMZ reflects on the past and present at “the world’s loneliest outpost.”

I am not a civil engineer. I am an infantryman. However, over two years leading the combined battalion, I learned a lot about bridges. Bridges are central to the geography and the psyche of the United Nations Command Security Battalion – Joint Security Area (UNCSB-JSA).

You must cross a bridge to get to the southern boundary of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), where the soldiers of the UNCSB-JSA live and work. You travel along Old Highway 1, which once connected the southern tip of Korea across the peninsula to the border with China. As you approach Panmunjom, you cross the Imjin River over the Tong-il Bridge.

Only South Korean citizens with special government permission may access the restricted area north of the Imjin. Eventually, the highway unwinds to Camp Bonifas, a place surrounded by rice fields, and the home of the UNCSB-JSA.

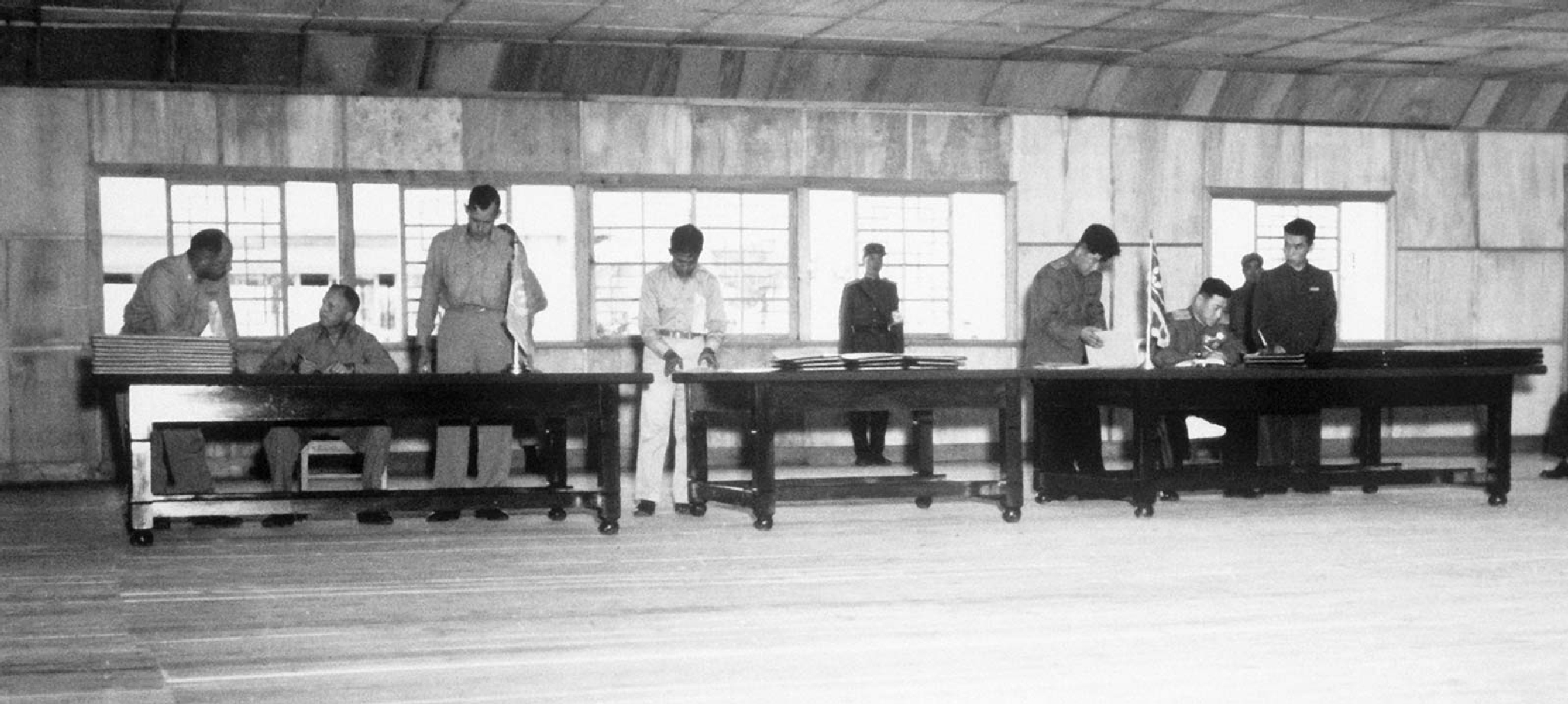

The Joint Security Area is a small space near the original tavern town of Nolmun-ri (nee Panmunjom) where the Armistice Agreement was negotiated during 158 formal meetings and more than 500 working level and informal meetings before finally signing an agreement on July 27, 1953. The combined U.S. and Republic of Korea Infantry Battalion that constitutes the UNCSB has protected diplomacy in Panmunjom since May 5,1952 – even before the 1953 armistice.

Signers of that 1953 armistice could hardly have imagined that it would be a lasting arrangement. That cease-fire was supposed to last only a few months to get all sides to agree on a peace treaty. But the Armistice Agreement has become an enduring document, holding strong for 67 years under the leadership of the United Nations Command.

And the JSA? It also serves as a bridge. A crossing on the border that has remained open, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, as a place where generals and diplomats could come to one day negotiate the terms of peace.

No Fences and No Return

Camp Bonifas is not the end of the journey. To get to our place of duty inside the JSA, we enter the DMZ itself and continue north on Highway 1. The last 2 kilometers to Panmunjom take us past the small bridges leading to the fields and homes of the farmers of Daeseong-dong village.

Daeseong-dong is the only village on the southern side of the border in the entire DMZ. Here, 200 residents – who all trace their family heritage to the Panmun Valley back before the Korean War began – live here. They abide by a strict set of regulations and security protocols as they farm land that directly adjoins North Korean rice fields.

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, or North Korea) is also authorized to maintain one village in the demilitarized zone: Kijong-dong, which is the sister city to Daeseong-dong.

Although their residents never interact, the hope has always been that once a peace agreement is signed, these two villages might unite. The peace would spread from here. There is no fence here. Only the tiny Sacheon Creek. Years of fear and uncertainty keep villagers from interacting. In some cases, siblings torn apart by war live only a few miles apart. They wonder what became of their relatives, and wait for the bridge to one day be open.

Just north of the village, and inside the actual Joint Security Area itself, we find another crossing: the Bridge of No Return. This crossing has been popularized in films such as SALT and Die Another Day. For the United Nations Command, however, it is a sacred reminder of how quickly a place designed to seek peace can become violent.

This bridge crosses the Sacheon and connects the North to the South. This crossing was the site of Operation Big Switch in the summer of 1953, and the earlier Operation Little Switch of April 1953. These events were the major repatriation operations of the Korean War, which allowed more than 100,000 prisoners of war to return to their respective nations. The operation was overseen by the United Nations Command and run by the Indian Army.

The name of this crossing is apt. It was at the Bridge of No Return that each servicemember was given a final choice at the entrance to the bridge. Stay, or go. If you chose the latter, you could never return to the other side again.

This crossing has seen homecomings and hard choices. It has also been the site of tragedy and high tensions.

It was at the Bridge of No Return that each servicemember was given a final choice at the entrance to the bridge. Stay, or go. If you chose the latter, you could never return to the other side again.

In the 23 years after the armistice signing, both the UNC and North Korea manned checkpoints at the bridge. Often called “the world’s loneliest outpost,” US and Korean People’s Army [KPA] soldiers interacted daily here. It was often a relationship expressed in taunts, and akin to bullying. The aggression often led to brawls, but never escalated beyond a few broken noses. The bridge was only used once again for an exchange in 1968, when the crew of the USS Pueblo was returned from captivity at this spot.

Things changed on August 18, 1976. Capt. Arthur Bonifas and Lt. Mark Barrett traveled to the Bridge of No Return to supervise the trimming of a large tree that was obstructing important views for the UNC security element. North Korean soldiers gathered in force and then attacked Bonifas and Barrett, brutally killing them at the foot of the bridge.

The UNC rejoinder to the murders was swift and heavy, and pushed the Korean Peninsula to the brink of war. Under the cover of an immense show of force, the large tree was cut down without incident, as President Gerald Ford and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger monitored the North Korean response from the White House.

After that day, both sides agreed that security elements from UNC and from DPRK would not intermingle, and the official Military Demarcation Line would not be crossed without express permission from the United Nations Command Military Armistice Commission (UNCMAC). Henceforth, the Bridge of No Return would be manned by opposing security forces only on opposite sides of the bridge, and never allowed to interact again.

Demarcations and Defections

Over the next 42 years, the UNC and KPA security battalions never interacted directly. In fact, the JSA became quite the attraction for visitors who wanted to glimpse what some call the last vestige of the Cold War.

Here, U.S. and South Korean soldiers continued to face off against the North Korean soldiers just across the border. Both sides were fully armed. Both sides took the most intimidating poses they could manage. President Bill Clinton famously described Panmunjom as “the scariest place on earth” after his visit.

There is no doubt that the attraction to visitors was the tension and the real sense of danger. But the UNC has worked hard to maintain Panmunjom as a place for dialogue. During the time when the security forces did not interact, the UNCMAC continued to maintain contact with the KPA. Through daily hotline checks, UNC maintained an open line for de-escalation and dialogue, and provided an opportunity for the U.S. government to pursue diplomacy.

Unfortunately, in 2013, the KPA stopped answering the daily calls. Yet UNC never stopped dialing, and never stopped seeking the space to pursue greater dialogue

Almost immediately after the sides agreed to prevent crossing and intermingling at the Bridge of No Return in 1976, the DPRK constructed another bridge to enter the Joint Security Area. Built in only three days, it quickly earned the nickname of “72 Hour Bridge.” (The KPA call it the Panmunjom Bridge.)

There is no doubt that the attraction to visitors was the tension and the real sense of danger. But the UNC has worked hard to maintain Panmunjom as a place for dialogue.

This crossing also has been the scene of recent unexpected drama with potential strategic implications. On an otherwise quiet Sunday afternoon in November 2017, KPA Sgt. O Chong Song drove his army jeep across the 72 Hour Bridge.

O’s KPA comrades did not know why he was driving into the JSA. By the time they did realize what was happening, O had driven straight to the Military Demarcation Line and crashed his jeep into a small trench. When his fellow countrymen finally realized a defection was in progress, they started shooting – 27 shots in all. Five of them hit their target, but O still managed to run across the border.

Once the shooting stopped, the United Nations Command Security Battalion rescued O and provided him with immediate medical care. He recovered from his wounds and now lives in Seoul. It is important to note that the UNC soldiers deliberately held their fire. As they were not the targets of the KPA, their mission was to defend Sgt. O once he crossed the border, but to otherwise de-escalate the situation.

The DPRK immediately reinforced the 72 Hour Bridge with a large mechanical gate to prevent such defections from occurring again. Tensions were high. Bridges were blocked. Strategic rhetoric from both sides was confrontational. The way forward looked uncertain.

New Opportunities

Had the defection incident led to more KPA or UNC deaths, perhaps the newfound détente of 2018 might not have occurred. Only six weeks after the incident, on January 1, 2018, North Korea’s Chairman Kim Jong Un issued his annual New Year’s message to his nation. This time, the tone seemed different. And within the next eight weeks, North Korea agreed to participate in the PyeongChang Olympics. The world even saw a unified women’s ice hockey team compete together.

The summit on April 27 that year between President Moon Jae-in and Chairman Kim marked a significant step towards the improvement of relations.

The United Nations Command worked closely with the South Korean government to ensure the Joint Security Area was a secure and appropriate venue for such a historic meeting. And for the first time in history, the North Korean leader walked across the border into South Korea.

The two leaders had multiple engagements that day, but perhaps none were as productive as when the two men shared tea, alone without their entourages. This meeting, bridging regimes and nations, took place on the JSA Blue Bridge. This humble location – affectionately nicknamed “Dobodari,” or “footbridge” – sparked critical dialogue between the two leaders.

As commander of the United Nations Command Security Battalion from June 2018 to June 2020, I had a close-up view of how these events opened the door to increased trust and confidence between UNC and KPA soldiers in the JSA. Our increased interaction paralleled the improved dialogue and cooperation at the strategic level.

The June 12, 2018, summit in Singapore between President Donald Trump and Chairman Kim further increased opportunities for local engagement. After the summit, the security battalion in Panmunjom prepared the flags and cases to repatriate 55 sets of remains from the Korean War. The UNCSB secured delivery of the materials into North Korea so the UNC remains could be flown home to Seoul and then to Hawaii with dignity and respect. Working with UNC and the DPAA to fulfill a never-ending promise to keep trying to bring home our fallen comrades was a tremendous honor for the UNCSB.

As commander of the United Nations Command Security Battalion, I had a close-up view of how these events opened the door to increased dialogue and cooperation.

Sometimes the new atmosphere brought unique surprises. On July 12, 2018, about three hours after UNCMAC had made yet another unanswered phone call on the hotline, the customary silence in the office was pierced by an old-fashioned telephone ringer. Everyone in the room looked at the phone, and then at each other. Nobody had ever heard it ring before. The UNC duty officer, a flight lieutenant from New Zealand, answered the phone.

Her KPA counterpart spoke as though there had not been five years of silence at all, informing her that he was checking the line. From then forward, as of this writing, the KPA and UNC have connected with each other twice a day – sometimes to coordinate actions inside the demilitarized zone, and at other times simply to confirm that the line is open, and someone is listening.

A Trilateral Turn

In September 2018, things began to move even more quickly in Panmunjom. President Moon and Chairman Kim signed a bilateral Comprehensive Military Agreement [CMA] that included numerous suggestions for how to leverage the Joint Security Area as an even better venue for peace.

Although the Armistice Agreement is the overarching and legally binding document that governs the Demilitarized Zone and the Joint Security Area, the CMA recommended measures that aligned with – and advanced – the goals of the Armistice Agreement. The United Nations Command supported the implementation of the CMA as a sign of its commitment to meeting armistice objectives and advancing the possibility for peace

Some of the key tenets in the CMA included: (1) the establishment of a trilateral commission consisting of UNC, ROK, and DPRK to manage changes to the JSA; (2) the removal of all weapons from the JSA; (3) sharing of surveillance feeds by both sides; and (4) the establishment of joint checkpoints where UNC and KPA troops would serve side by side.

On October 16, 2018, the trilateral commission held its first meeting in the Joint Security Area. I was privileged to join the UNCMAC secretary, Col. Burke Hamilton, and Col. Shawn Burke of Britain at the table for negotiations. A schedule was proposed, and the joint demilitarization and verification was coordinated. For the next three weeks, the soldiers of the UNCSB-JSA conducted extensive demining operations, and prepared the heavily armed checkpoints and guard posts for the withdrawal of weapons and ultimate closure.

During this time, I met and shook hands with my KPA counterpart – a first for opposing security battalion commanders since 1976. In mid-October, I entered North Korea with other members of the trilateral commission to conduct examinations of proposed locations for the joint checkpoints. These early interactions with the KPA were professional, but they always felt scripted.

After three weeks of demining and preparation, the United Nations Command Chief of Staff, Maj. Gen. Mark Minihan, stood on the Military Demarcation Line on October 25, 2018, and gave the order to complete the demilitarization of the Joint Security Area. For the first time in its existence, the troops protecting Panmunjom no longer carried weapons. The guard towers now sit empty.

Over the next two days, as part of the trilateral commission, I participated in a mission to inspect and verify demilitarization on both sides. The first part of the day took place in North Korea. Unsure of what to expect, we were surprised by the openness and cooperation displayed by the KPA. Everything we requested to see was shown to us, including underground tunnels, the KPA operations center and their barracks. As the hours wore on, the professional interactions led to some expected small talk. During a break, ROK, U.S., and North Korean leaders even shared cigarettes and talked about family and common military experiences.

The next day, as the south side of the JSA was inspected, the KPA noticed a ramp into a building. Knocking on the ramp indicated that it had a hollow center. When they mentioned that this might be an area where newly unauthorized weapons might be concealed, we found a crow bar and offered to pry it off. This gesture satisfied their concern, and before the tool was deployed, KPA representatives declared: “No. Stop. Thank you. You don’t have to tear it up. We trust you.”

As the hours wore on, the professional interactions led to some expected small talk. During a break, ROK, U.S., and North Korean leaders even shared cigarettes and talked about family and common military experiences.

The inspection moved to the Bridge of No Return. Satisfied that the old guard post was empty, the KPA members of the party were invited to read the memorial plaque to Capt. Bonifas and Lt. Barrett. After they did so, the representatives from North Korea said it seemed to commemorate a violent event, and perhaps should not be situated in a place of peace. The UNC members politely but firmly declared it would stay, telling the KPA “We can move towards peace, but we must remember our history.”

After a long pause, a KPA colonel stated: “I agree.”

Building Trust

Over two days, the members of the trilateral inspection team spent about 16 hours together. Each guard post inside the JSA was sealed jointly, and the US, ROK and DPRK commanders all initialed the seals on the doors and windows. In a gesture designed to build trust and confidence, each side kept the keys to the opposite checkpoints. While all involved knew that a swift blow with a hammer is all that we needed to reenter respective checkpoints, the gesture was important.

During the months of November and December 2018, UNSCB soldiers spent countless hours with KPA counterparts in over 30 engagements. Our side always brought young soldiers, non-commissioned officers, and soldiers of every race and gender to these meetings to demonstrate what an army looks like in a democracy.

We coached our troops to be tough but approachable. Prepared for violence, but ready to engage with kindness. These long days led to discussions about families, growing up, education, art and sports. We discovered that the KPA contingent loves Frisbee and Johnnie Walker. They hope their children would choose successful professions like engineering. They shared with us how they celebrate holidays.

At the Korean New Year’s holiday, I asked my counterpart across the DMZ what he planned to do. He said his wife was planning to cook a large meal for extended family, and they would follow the meal by walking through town to visit statues of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il. This was a common theme during all of our interactions. These men were willing to reveal their humanity, but they always – always – ensured that we understood their commitment to the regime.

There are a few memories I will never forget. I knew that Chairman Kim was a big fan of the Chicago Bulls teams of the 1990s, so I let on early that I had grown up in Chicago and remain a basketball fanatic. They asked me numerous questions about Chicago, about Michael Jordan, and about the foods and cultures for which Chicago is so well known. I am certain that my love for my city made it into my targeting file because as new KPA officers entered the mix, they would always ask me about Chicago.

Once, during a particularly tricky part of construction and deforestation on the other side, we offered assistance to the KPA troops performing the difficult tasks. They asked us why we cared so much about North Koreans. After we told them we were in this together, and that our success meant greater chances for peace, an old KPA colonel said, “You know, you are different than we were taught you would be.”

As I smiled, he continued: “In fact, my grandchildren are in school and they learn to count by saying: “One American bastard. Two American bastards. Three American bastards.” I laughed, and said I hope that might change. Slowly and cautiously, both sides were building bridges.

Soldiers from the DPRK were willing to reveal their humanity, but they always – always – ensured that we understood their commitment to the regime.

Yet some bridges remained too far to cross. Around Christmas 2018, we invited the KPA to share a meal with us in the historic buildings right on the Military Demarcation Line. We sent an invitation, which they acknowledged. We never expected them to show up, but with a degree of hope on Christmas Day, we entered the blue buildings of Panmunjom. We opened the windows and the doors and laid out a feast.

We waited for an hour. Eventually two KPA soldiers came down and photographed us from a distance. We left feeling dejected. A few days later, we realized that the meaning of our gesture had not been lost. Even in the absence of a meeting, trust and confidence was slowly growing. A North Korean major approached me during a meeting and said: “Thank you for inviting us to your Christmas. We wanted to come, but it wasn’t possible.”

What Now?

After the concerted flurry of activity in the fall of 2018, routine interactions diminished in early 2019. Yet a palpable difference in attitude remained. Whereas before 2018, every encounter at the JSA involved looking tough and posturing, the trust-building from the fall of 2018 introduced an occasional wave and, if you looked close enough, a slight smile. It was clear they were not authorized to have casual conversations with us, but it was also clear that they no longer felt the need to try to intimidate us.

After the Hanoi summit between President Donald Trump and Chairman Kim in February 2019, local interactions fell off even more. Tactical leaders on the North Korean side likely took their cues from their political leaders. We took our orders from our generals, and continued to seek ways to build trust and confidence with the KPA at the tactical level.

However, we all found ourselves working closely together again during a burst of activity around the spontaneous meeting between President Trump, President Moon and Chairman Kim inside the JSA on June 30, 2019. This time, as we secured the Joint Security Area and observed our Commander in Chief enter North Korea, I was impressed (but not surprised) by the professionalism of the US Secret Service, the ROK presidential protection and the DPRK presidential protection. They had a joint mission to protect their leaders , and they worked exceptionally well together. Common goals have a way of revealing common humanity.

As 2019 drew to a close, and 2020 entered with a storm, the emergence of African Swine Fever, and then COVID-19, has created unexpected space between all of us – limiting both access to the JSA and interactions within it. .

“Thank you for inviting us to your Christmas. We wanted to come, but it wasn’t possible.”

It has been a few months now since we engaged directly with our KPA counterparts. In the recent weeks, rhetoric from the DPRK has once again ratcheted up. The United Nations Command remains committed to upholding the Armistice Agreement. The opportunity for dialogue and de-escalation – the bridge – always exists in the Joint Security Area.

Building these bridges between UNC and KPA Soldiers creates the conditions for our generals, our diplomats and our policy makers to come to Panmunjom and safely work towards mutually beneficial policies and denuclearization, as well as the more permanent peace that has been sought since 1953.

Lt . Col. Sean Morrow served as the Commander of the United Nations Command Security Battalion from 2018-2020. Morrow is a graduate of the U .S. Military Academy, Boston College, and the University of Chicago where he is a currently a Ph.D. candidate in Political Science. He is honored to serve as the president of the West Point Class of 2001. Morrow lives with his wife, Meghan, and their three sons in West Point, New York.

The opinions expressed in this paper are the author’s own, and do not represent the official position of the Department of Defense.

(Cover photograph: The Bridge of No Return. UNCSB / Cho Yong-won)