Fall 2011

Heroic Reader

– Gerald R. Russello

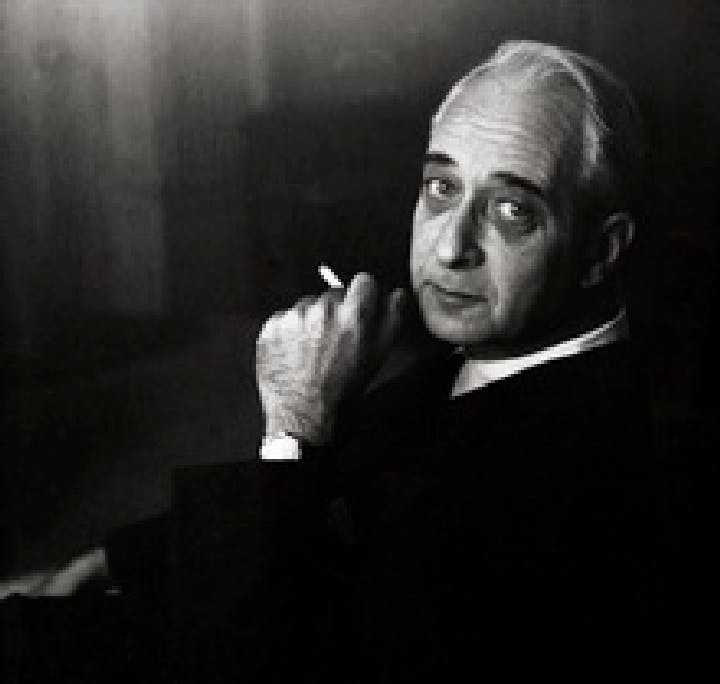

Twenty years ago, asking why Lionel Trilling mattered would not have seemed necessary.

Twenty years ago, asking why Lionel Trilling mattered would not have seemed necessary. Trilling (1905–75) was a professor at Columbia University for four decades, author of The Liberal Imagination (1950) and other essential works of 20th-century criticism, and an editor—along with poet W. H. Auden and historian and critic Jacques Barzun—of the popular Reader’s Subscription Book Club series in the 1950s. His influence was palpable. Although he left no disciples behind, critics such as Cynthia Ozick and neoconservatives including Irving Kristol show his influence.

Yet, as Adam Kirsch notes in this concise study, Trilling is in danger of being dismissed or, worse, mocked. His emphasis on the canonical texts of English literature doesn’t jibe with our multicultural sentiments, and his conviction about the autonomy and privileged place of literature (specifically, the long-form novel) has struck many contemporary critics as schoolmarmish and passé. Books are dead; who needs literary critics, especially those who (in the view of Trilling critic Louis Menand) “worried too much about culture” and were raised in an environment permeated by Modernism and Marxism, neither of which has the cultural weight it once did?

To Kirsch, a well-known poet and essayist and an accomplished critic in his own right, these indictments oversimplify Trilling’s work. He places Trilling alongside figures such as Isaiah Berlin and Hannah Arendt as representing a liberalism committed to pluralism and difference. Unlike those two, Kirsch argues, Trilling advanced this liberal vision by engaging with literature rather than political philosophy or history.

Writing as a young man in the 1920s and ’30s, Trilling mouthed some of the anti–middle- class platitudes of the Left, and thought literature should be subservient to communist ideology. As he matured, however, he staked out the opposite positions in books such as The Liberal Imagination and, later, Sincerity and Authenticity (1972). Like his models E. M. Forster and Matthew Arnold, Trilling “tried to vindicate literature as a social good, while preserving its imaginative independence from utilitarian pressures,” Kirsch says.

Kirsch deftly untangles this intellectual journey, freeing Trilling from the collective opinions of a generation. For example, contrary to the general view that The Liberal Imagination is a political book, Trilling explicitly made the liberalism alluded to in his title at once “an emotional tendency, a literary value, an intellectual tradition, and a way of being in the world,” Kirsch observes. Indeed, he makes a compelling case that the book reflects Trilling’s rejection of a simplistic equation of literature with ideology in favor of a nuanced liberal imagination suffused with “complexity and difficulty,” which the reader must confront in the great works of modern literature. Trilling’s liberalism, therefore, was an interior conversation—reader to author.

For most of his book, Kirsch makes a case for Trilling as an important historical figure, if not a figure of current importance. The Modernists who held the attention of Trilling’s contemporaries are largely without an audience today, and the agonized arguments over Modernism and communism among Partisan Review writers will fail to move a new generation to pick up Trilling’s books. But in the last chapter, which he titles “The Reader as Hero,” Kirsch cleverly pits Trilling against the still-influential critic Susan Sontag.

In the 1960s, Sontag opposed many of Trilling’s literary values in favor of an “erotics of art” that offered no standards with which to discriminate among artistic experiences; the emerging “one culture” she championed would be dedicated to “seriousness” as well as “fun and wit and nostalgia.” What Sontag did not anticipate was that this culture, in breaking down the boundaries between popular art and high culture, would transform art from something experienced internally to something to be consumed. Kirsch finds Sontag’s legacy in brand loyalties and commercial purchases: art as reflecting whom we want to be perceived as by others, rather than whom we are trying to become. Trilling’s unique encounter with the work of Henry James is superseded by Andy Warhol’s endlessly replicable soup cans.

Trilling long argued that the individual reader’s struggle with great literature formed character, and that the 1960s counterculture and the global capitalism it colonized replaced this struggle with a quest for external status markers. He regarded with alarm the same cultural shifts Sontag celebrated—until she eventually grew chastened at their destructive possibilities. Trilling’s enduring value, Kirsch concludes, is that despite the rise of a consumerist sensibility to replace the liberal self, his brand of “readerly heroism is always a possibility for those who believe in it.”

* * *

Gerald J. Russello is the editor of The University Bookman. Reviewed: Why Trilling Matters by Adam Kirsch, Yale University Press, 185 pp.

Cover photo courtesy of Wikipedia