Spring 2021

Pandemics - Then and Now

– John M. Barry

The lessons of 1918 could have helped the world in 2020. Why did we forget them?

2020 was not my introduction to pandemics.

As the author of an account of the 1918 influenza pandemic, and involved in planning of U.S. public health responses beginning in 2004, I have thought deeply about these issues.

So it’s no surprise that in the past year, I have been asked over and over to compare that previous pandemic to our COVID-19 crisis, and what lessons from 1918 might apply now.

There are two main lessons from 1918. As I wrote in the afterword to my book: “[The most important] lesson of 1918, a simple one yet one most difficult to execute, is that those who occupy positions of authority in a society must retain the public’s trust. The way to do that is to distort nothing, to put the best face on nothing, to try to manipulate no one.”

The second lesson? Public health measures – the so-called “non-pharmaceutical interventions” (NPIs) of social distancing, proper ventilation (very important and not emphasized enough in messaging from public health leaders), masks, hand-washing, and so forth – actually work. Those two lessons are intertwined. Public health measures work only if people both use them and sustain that use. In a free society that happens only when leadership tells people the truth and convinces them to cooperate. Since COVID-19 surfaced, the leadership of some nations did just that. Others did not.

There has been an immense amount of detailed reporting about what went wrong in such countries as the United States, Brazil, Iran, Mexico, or others, or what went right not only in countries with economies as advanced as Japan, but in countries with as few resources as Kenya possesses. What leaps out from this evidence is that death tolls in this pandemic correlate directly with how seriously – or not – a particular nation took the lessons taught in 1918.

For those who argue that such countries as South Korea, Singapore, Thailand, and Taiwan succeeded because of their culture, and that compliance with public health measures was bound to fail in more individualistic western countries, one should consider Australia, which is every bit as western and as individualistic a culture as the United States.

Public health measures work only if people both use them and sustain that use. In a free society that happens only when leadership tells people the truth and convinces them to cooperate.

At this writing, Australia has 909 deaths. The U.S. population is thirteen times that of Australia, so a comparable death toll here would be fewer than 12,000 deaths. But the U.S. has passed 500,000 deaths and had a peak average of over 3,000 deaths daily; between October 16 2020 and March 31 2021, Australia has averaged 0.024 deaths per day – a total of four deaths in five and a half months.

It is the same virus in both countries. Both countries have the same tools. The difference is leadership.

And did Australia pay a higher economic price to save lives? No. The two economies have performed the same in 2020, and the OECD projects that growth over the next two years in Australia will significantly exceed the U.S. – 4.2 percent to 3.5 percent in 2022.

That’s where we stand now. But let’s look deeper. How do the two viruses and the two pandemics compare? What are the lessons we should learn this time?

Almost Twins?

The 1918 pandemic killed an estimated 50 to 100 million people; adjusted for population that would equal 225-450 million today. Most of the deaths probably came from secondary bacterial infections, so modern medicine might have cut the death toll in half – if supplies and intensive care beds were available. (Today, case fatality for bacterial pneumonia following influenza is 6-8 percent, roughly one-quarter of the rate in 1918.) Even the worst case projections for COVID-19 are nothing like that.

Both the 1918 influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing the disease known as COVID-19, transmit exactly the same way, chiefly through virus expelled when shouting, talking, or, for that matter, breathing, either in droplets, which fall to the ground fairly quickly, or smaller and lighter aerosolized packets of virus, which can float in the air for hours like dust motes. Both viruses primarily attack the respiratory system. Both can bind to cells in the upper respiratory tract, which make them highly transmissible, and both also can bind to cells deep in the lung, which can make them lethal – because victims start out with viral pneumonia.

The symptoms are also similar. Both viruses commonly cause dry cough, body aches, headache, diarrhea, and fever. Both viruses can ignite, and kill through, a cytokine storm – which occurs when the immune system throws every weapon it has at the virus but the battlefield is the lung, reminiscent of the comment by an American officer during the Vietnam war that he had to destroy the village to save it.

In addition, though both viruses primarily attack the respiratory system, both the 1918 influenza virus and SARS CoV-2 have particularly pronounced neurological and cardiovascular impacts, and, unlike other influenza viruses that plague humans, can damage virtually every organ in the body. Both viruses also cause illness which can linger for extended periods. It is not entirely clear in either case how much damage comes directly from the virus itself infecting these organs, and how much comes from the immune system’s attempt to defend the body. To the extent the immune system caused the problems, the lingering impact and sequelae could be identical.

The effects could be pronounced. Months after supposedly recovering from influenza, poet Robert Frost wondered, "What bones are they that rub together so unpleasantly in the middle of you in extreme emaciation... Here it is as late as this (1919 A.D.) and I don't know whether or not I'm strong enough to write a letter yet.”

The Cincinnati health department provided more quantitative assessment. In the first months of 1919, it noted an extraordinary number of prominent citizens who had recovered from influenza died suddenly from other causes. It subsequently examined 7,058 influenza victims and found 5,264 needed some medical assistance. Without the benefit of modern scans or blood markers, it also found 643 with heart problems. The 1918 virus was commonly linked to neurological problems as well, some of which did not even surface until the 1920s. And while the question has excited immense interest, it is far too soon to know how long-lasting COVID-19 damage can be, and whether and what further sequelae may eventually develop.

What leaps out from the evidence is that death tolls in this pandemic correlate directly with how seriously – or not – a particular nation took the lessons taught in 1918.

Like all viruses, especially those in which RNA carries their genetic information, both viruses mutate. Influenza does so at a much faster rate. The 1918 virus changed dramatically between the first wave in Spring 1918 and a second wave in autumn of that year, becoming both more infectious and much more lethal. It changed again early in 1919, becoming somewhat milder. In combination with the immune system becoming better able to deal with it, the 1918 virus continued its march toward mildness; its descendants circulated as ordinary seasonal influenza until 1957, when it was replaced by a new pandemic virus, although some of the genetic code of the 1918 virus still circulates today.

With SARS-CoV-2, the first important variant emerged early in 2020 in Europe. This version spread worldwide, outcompeting the original virus from China. Next came the so-called UK variant, B.1.1.7, which was more transmissible and approximately 60 percent more lethal; this surged in the United Kingdom and throughout Europe beginning in late 2020, and spread rapidly in the U.S. beginning early in 2021.

Also important were two variants which emerged independently in South Africa and Brazil, and had great similarities. Like the UK variant, they were more transmissible and seem to be at least incrementally – and possibly more than incrementally – more virulent, but more worrisome was the fact that they at least partially evaded the first generation of vaccines. At this writing, variants have emerged in New York and California that share these traits.

A final similarity can be found not in the virus itself, but in the response of world leaders. In 1918, governments of warring countries minimized the pandemic. In the U.S., officials told outright lies, for example, saying, “This is ordinary influenza by another name.” They did so because they feared the truth would demoralize the public and damage the war effort. President Woodrow Wilson never made any official statement whatsoever about it, withdrawing himself from addressing the pandemic even more than President Donald Trump did in 2020. For these two chief executives, the motivation differed, but the results were similar.

Transmissibility and Time

Similar as the 1918 virus and SARS-Cov-2 are, they also have four very important differences. The first has already been mentioned: the 1918 virus was much more lethal. Case mortality in the West was probably 2 percent to 2.5 percent, but it was much higher, probably 6 percent to 8 percent, in the developing world. The disparity arose not because medical care was any better in the West, but because people in less developed areas had little or no prior exposure to seasonal influenza viruses and therefore enjoyed no cross-protection.

Another key difference is transmissibility. COVID-19 is significantly more transmissible than ordinary influenza, and probably is more transmissible than the 1918 virus. The reproductive number for seasonal influenza is 1.28 – one person infects 1.28 more people – according to the average of numerous studies. The average of several studies of the 1918 virus put its reproductive number at 1.8.

Recent studies put COVID-19’s natural reproductive number – with no public health measures intervening to slow its transmission – between 2.5 and 3. The several variants discussed above seem to be 40 percent to 70 percent more transmissible even than that. Again, public health measures – primarily social distancing and masks – can still bring this number down to less than 1. But as the natural reproductive number rises, transmission becomes increasingly difficult to control without vaccines – or via non-medical interventions.

The two viruses also differ in asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic transmission. This does occur with influenza, but it is not the primary driver of spread. By contrast, a study of COVID-19 by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control found that 59 percent of cases come from people who do not have symptoms at the time. (A further breakdown indicated 24 percent of cases transmitted by people who never develop symptoms, and 35 percent from those who later developed symptoms.) Even in 1918 scientists established that a mask on the sick protected healthy people; this remains true and is the chief reason why mask use by the public matters for COVID.

The most dramatic difference, however, is that the 1918 virus killed otherwise healthy young adults in large numbers, peaking near age 30, with well over 90 percent of the excess mortality occurring in people younger than 65. Other influenza pandemics also lowered the average age of the dead. The 1957 and 1968 global pandemics saw only a slight downward trend, but the 1918 and the 2009 pandemic viruses were very similar. In 2009 the peak age for death was 30-39.

COVID-19 is significantly more transmissible than ordinary influenza, and probably is more transmissible than the 1918 virus.

Seasonal influenza also attacks children, but not like the 1918 virus; in 1918 children aged one to four years of age died in numbers equal to today’s all-cause mortality – the combined deaths from all drownings, accidents, cancer, heart disease, infections, murder, etcetera – over a period of twenty-three years. Children aged five to nine years old did not fare much better.

COVID-19 does the opposite. Children die very rarely from COVID-19, the overwhelming majority of deaths occur in people older than 65, and as age increases, so does case mortality.

The viruses of 1918 and 2020 also differ in the fourth dimension: time. This is hugely important. The incubation period for influenza is generally one to four days, and most people get sick on day two. For COVID-19, the incubation period ranges from two to fourteen days, and most people get sick on day five or six. Influenza symptoms hit suddenly, and people are usually sick for three or four days. COVID-19 comes on gradually; it may take over a week after the first symptoms before serious complications such as shortness of breath develop. Yet deterioration can be very rapid once the virus takes hold. Recovery from illness also takes longer.

.jpg)

Serial transmission of the disease – transmission from one person to another to another to another – also takes longer. In 1918 perhaps two-thirds of the deaths worldwide occurred in a twelve week period between late September and late December, and the disease passed through any given community in six to ten weeks, and sometimes as quickly as three or four weeks. Once it was gone it was gone; the 1918 virus did not percolate at a low level. A third wave did hit many areas – not all – in March and April 1919, but these cases emerged unexpectedly, and in between these two periods, there was very little influenza activity.

As we have seen in the series of sustained global outbreaks, this is not the case with COVID-19. Even without implementing any public health measures to interrupt transmission, this pandemic would have stretched out for many months, not just weeks. Those measures were imposed to save lives, and they did save lives, probably hundreds of thousands of lives in the U.S. alone and millions worldwide. But these actions also made the outbreak last longer than it would have otherwise.

As a result, while 1918 was a much more intense experience, without the benefit of Zoom or television, and it killed many more people, COVID-19 has caused much more severe and much longer lasting economic damage. And, in some ways, more than a year of limited physical contact with people, many months of school closures, and in some cases almost total isolation have also caused more societal stress than the few weeks of hell in 1918.

Data and Destiny

While the similarities may have suggested that we might learn from history, the differences between the viruses of 1918 and 2020 – particularly the fact that COVID primarily kills the elderly and the economic pressure created by the duration of the pandemic – have combined to have a significant impact on public policy.

In 1918, the public was lied to, and the lies mattered. Initially, when the public still believed official pronouncements, lies killed people who exposed themselves. But soon deaths became too common for anyone to trust what the government said. I believe that ultimately society is based on trust, and as trust dissipates, society begins to fray; one saw this alienation in 1918 both in large cities and rural communities – even to the extent that people starved to death because others lacked courage to bring them food.

In the past year, many articles have compared pushback against masks in 1918 to 2020, but the reality is that opposition to public health measures in 1918 has been overstated. With death everywhere, people accepted virtually every measure that might help. Sometimes, as in San Francisco, when regulations were lifted and then re-imposed, there was unrest. But even that episode was trivial compared to what has happened in 2020, and it had nothing to do with partisanship.

In the U.S., as in Germany, France, Brazil and elsewhere, over the past year much of the opposition to public health measures has been linked closely to the political right. These movements have exploited arguments from a minority of public health experts, many of whom support masks and distancing advice but believe that the benefits of closure orders do not justify their economic and health costs. A number of these experts proposed pursuing herd immunity through natural infection, while protecting vulnerable elements of the population and letting the economy operate with few, if any, restrictions, and allowing the virus to infect younger people. This became the de facto policy of the Trump White House (although it shied away officially from the term “herd immunity”) and its political allies, in direct contrast to advice from its own experts.

But deciding between the economy or public health was always a false choice. They are dance partners, and public health takes the lead. There is significant evidence to demonstrate this.

Economists at MIT and the Federal Reserve Board looked at data from 1918 and found that cities that closed down earlier and stayed closed longer had better economic recoveries. And a study by the generally conservative National Bureau of Economic Research looked at countries around the world and correlated lower death tolls – the result of effective NPIs – with stronger economic performance.

Other research underscores this delicate dance. One study reviewed economic data and cell phone data tracking movements and found that the economic collapse occurred before governments issued closing orders, demonstrating that concern over disease, not government controls, initially shut down the economy. The restaurant business also provided insights. Reservation booking company OpenTable reported that restaurant business in Germany and the U.S. was down over 90 percent from the previous year in March and April 2020. After that, however, they diverged widely: by mid-August both countries had largely reopened, but Germany had gained control over outbreaks and the U.S. had not. As a result, German restaurants were then doing 9 percent more business than the preceding year; U.S. restaurants were still down 50 percent.

And what about achieving herd immunity through natural infection, while imposing few limits on business or activities and trying to protect the vulnerable? Sweden has provided a case study. In the spring of 2020, the architect of the approach stated that its effectiveness could not be evaluated until months later. But now, the returns are in: Sweden’s per capita death toll was almost six times Denmark’s and nearly twelve times Norway’s.

Deciding between the economy or public health was always a false choice. They are dance partners, and public health takes the lead.

These deaths did not buy economic prosperity, either. Sweden’s economy fell 8.6 percent in the second quarter, compared to Denmark’s 6.8 percent and Norway’s 5.1 percent. And as the months passed, and cases surged in late 2020 in Sweden just as they did elsewhere in Europe, that nation moved further and further away from its own policy. In December 2020, it finally all but abandoned it, finally recommending (but not requiring) masks and authorizing aggressive closures.

So what are the lessons from the past year? They are the same ones that 1918 taught: first, tell the truth, second, public health measures work. Hegel said what we learn from history is we learn nothing from history. Maybe the world will prove him wrong next time.

John M. Barry is author of The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History (Penguin Books) and Distinguished Scholar at the Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine. This article is adapted from a new afterword for The Great Influenza.

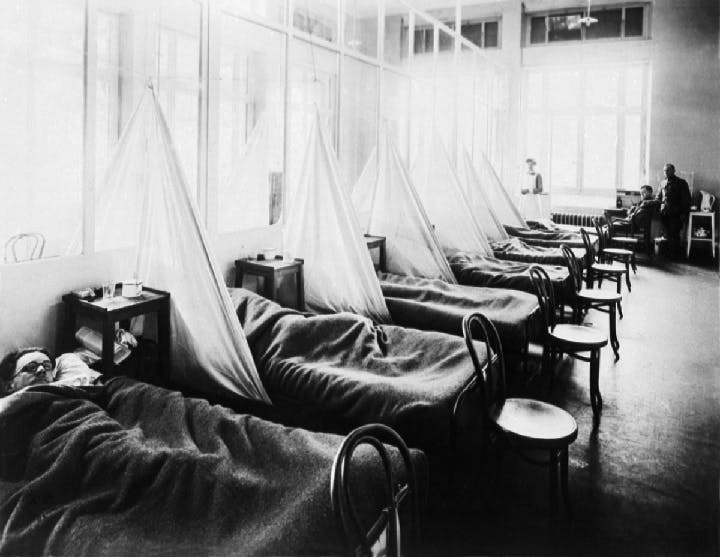

Cover photograph: Influenza Ward No. 1 , U.S. Army Camp Hospital No. 45, Aix-Les-Bains, France, (U.S. Army Corps /National Museum of Health & Medicine)