Summer 2020

Guns and Hunger

– Jean H. Lee

Reflections on one South Korean family's journey through the conflict and beyond.

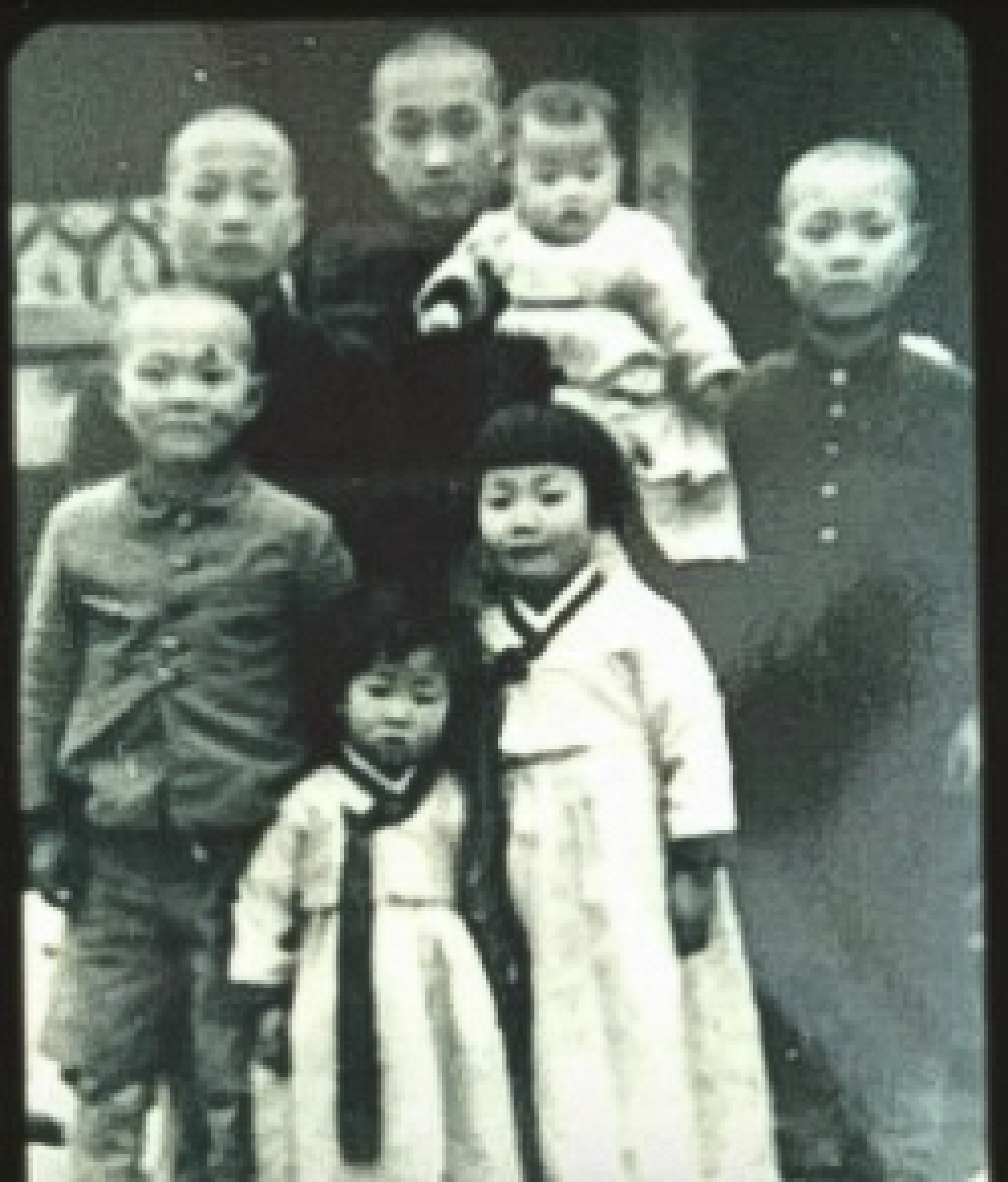

On the morning of June 25, 1950, my father, the mischievous fourth son of a prosperous South Korean businessman, was fast asleep in the family’s home in Gangwon Province. It was a quiet morning in an otherwise bustling home where his mother watched over four sons and two daughters, with another on the way. Her husband was in Seoul for work with their second son, then attending high school in the capital.

Times were tense. For months, skirmishes with North Korean soldiers had been taking place along the 38th Parallel, a stone’s throw to the north, and South Korean troops were busy fending them off. Despite the constant threat of war, my father recalls an idyllic childhood in the big house in Chuncheon, swimming in the river in the summers and ice skating in the winters.

But in the predawn hours of June 25, North Korean troops massed along the border dividing North and South, and staged an invasion by land and air that stretched from west to east. Seoul, the South Korean capital, was their main target.

As North Korean soldiers closed in, my grandfather and his son jumped into a rented truck. They made it across the Han River before the bridge was bombed to slow the communist advance.

Meanwhile, in Chuncheon, my pregnant grandmother made a split-second decision to flee on foot with the children — including my father — and two household helpers.

For the next eight months, the family faced hunger and starvation as they crisscrossed the country dodging North Korean troops and bombings by the US-led United Nations forces. My grandmother lost one son and gave birth to a daughter. Three of my father’s uncles went missing.

For the next eight months, the Lees faced hunger and starvation as they crisscrossed the country dodging North Korean troops and bombings by the US-led United Nations forces.

When the fighting came to a halt with an Armistice Agreement three years later, on my father’s 13th birthday, July 27, 1953, the family returned to Seoul to rebuild their lives.

My family’s wartime tale is not particularly remarkable; their harrowing experience could be told a million times over. This is not a tale of military heroism, or even one of selfless sacrifice. It is simply the story of one family of ordinary Koreans who survived the three cruel and crushing years of war that killed nearly a million South Korean civilians.

In looking back at the AP’s wartime dispatches, I was dismayed to see the people of Korea referred to routinely as “peasants,” a demeaning term that stripped them of identity and diminished the significance of their lives.

On this 70th anniversary, as we honor the veterans who fought on their behalf, I want to put names and faces to these “peasants,” starting with my family.

The Fall of Seoul

Today, North Korea remains one of the world’s poorest nations even as the regime has built one of most dangerous nuclear programs on the planet. South Korea, meanwhile, has risen in global stature to become the world’s 12th-largest economy, and a leader in technology, healthcare and pop culture.

But in 1950, South Korea also was impoverished. It was struggling to transition to democracy after more than 35 years of colonial oppression by the Japanese and, before that, centuries of a feudal monarchy.

Five years earlier, after surrendering during World War II, Japan had finally withdrawn from South Korea. In its wake, the Soviet Union sent soldiers from the north while the United States brought in troops from the south, dividing Korea at the 38th Parallel.

The Soviets installed the young Kim Il Sung in Pyongyang. In September 1948, he established the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and became its first leader. The United States backed the American-educated Syngman Rhee in Seoul, who was elected president of the new Republic of Korea. Both declared their administrations the legitimate government of Korea.

By early 1950, my paternal grandfather, Lee Pom-rae, owned a string of gasoline stations in Gangwon Province, in South Korea’s northeast. Young, successful and well-connected, he also was politically active, funding the local office of the ruling party, supporting President Rhee and donating generously to the Red Cross. He also had political aspirations; he ran for a seat in the new National Assembly in March 1950 — and lost.

On June 25, he was in Seoul on business with son Hak-chong, who was attending school in the capital. As the North Korean troops advanced, my grandfather tried frantically to reach the family in Chuncheon. But the roads northeast were blocked, so they drove south.

“As we crossed [the] Han River and drove southward, the road became completely filled with evacuating traffic and refugees, making it impossible for a vehicle to drive on,” Hak-chong, known to me and my cousins as Uncle Hank, recalled in a memoir written before his 2016 death. “No sooner (had) our truck slowed down than the refugees swarmed over and completely packed it. Refugees continued to pour into the road, and the traffic was virtually immobile.”

It took hours to drive a few miles to Suwon, on the capital’s southern outskirts. “Just before the daybreak, we heard a big, big blast from north.” A South Korean military engineer had been ordered to blow up the Han River Bridge in a bid to stop the North Korean advance, killing hundreds of civilians and soldiers trying to flee south. “It meant the North Korean takeover of Seoul was imminent, if not already taken over.”

Seoul fell to the North Koreans in just three days.

Giving up hope of reaching Chuncheon, my grandfather continued south to Yeongdong, his wife’s hometown in North Chungcheong Province. There, my grandmother’s family, the Songs, were landowners with a sprawling traditional Korean “hanok” estate. The Songs descended from an illustrious poet, philosopher and statesman, Song Si-yeol, and for hundreds of years had maintained a traditional Confucian lifestyle.

“As we crossed [the] Han River and drove southward, the road became completely filled with evacuating traffic and refugees, making it impossible for a vehicle to drive on."

They arrived safely but felt shame at facing Grandmother Song without the rest of the family. They had no idea whether the rest were dead or alive.

In Chuncheon, meanwhile, my grandmother, Song In-hyeon, heard on the radio that troops were fighting in nearby Cheorwon, just 15 miles away. The government urged residents to evacuate.

“She knew that the communists had my father on the top of their enemy list since he was a National Assembly candidate for Syngman Rhee’s National Party, which meant that my father and my family would be either executed or taken political prisoners if they were in Communists’ hands,” Uncle Hank wrote.

With no time to pack or prepare provisions, my father recalls that they fled empty-handed, with just the clothes on their backs. With the roads to Seoul closed, they headed south, crossing the surging Hongcheon River and climbing the steep Taebaek mountain range on foot.

“It was a throng of people, all the way from Chuncheon over the mountain, the river, on foot,” my father recalls.

It took them two full days to reach the town of Yeoju, about 40 miles away. Along the way, my father and his siblings relied on the generosity of villagers for food and shelter. Too weak to walk, my grandmother rode on the back of a family helper; none of them knew she was pregnant. From Yeoju, they continued onto Suwon, staying overnight at the home of a business associate. They caught the last train out of that city before rail lines were cut off.

With no time to pack or prepare provisions, my father recalls that they fled empty-handed, with just the clothes on their backs.

In Yeongdong, there had been no news for days about what happened to the Chuncheon family. But on June 30th, there was a hopeful sign: a groundskeeper spotted someone waving a white cloth from a cargo train arriving at Yeongdong Station.

“Soon after, with the watch dogs barking loud, a bunch of beggars … showed up,” Uncle Hank wrote. “There they were, all nine of them, looking horrible, exhausted, but happy beyond description! We couldn’t believe our eyes. It was like a dream.”

The Lee family was reunited. Eventually, dozens of relatives from the Song clan descended upon their ancestral home, seeking refuge at the 99-room estate. (Only the king could have a home with 100 rooms, under Joseon Dynasty rules.)

But the respite was short-lived. As the North Koreans pushed southward, my grandfather and his older sons headed farther afield to look for safer accommodations for the family. They were cut off when the North Koreans captured Yeongdong on July 25, outmaneuvering the newly arrived U.S. forces.

At one point, my Uncle Yong-chong narrowly escaped death when U.S. soldiers trained their machine guns on him and other South Koreans in a bid to flush out communists suspected of hiding in their midst. The US attacks on civilians in the Yeongdong hamlet of Nogeun-ri were revealed in a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative story about the Korean War massacre.

“There they were, all nine of them, looking horrible, exhausted, but happy beyond description! We couldn’t believe our eyes. It was like a dream.”

On another occasion, the family took in two thirsty, hungry American soldiers fleeing North Korean troops. Unable to tolerate the spicy Korean food, the Americans left to look for sustenance — and were likely taken prisoner or killed, my father says.

In Yeongdong, meanwhile, food became scarce, even for the well-to-do Songs. “There were so many of us that we had to leave. So many people to feed,” my father recalls.

In late July, his mother decided to take the younger children to Okcheon, my grandfather’s ancestral hometown, outside the central city of Daejeon. There, they sought refuge in the sarang-bang, one of the outer rooms, of a grand home in Okcheon said to have once belonged to the family.

Tragedy in Okcheon

Okcheon was a dangerous place to be in the summer of 1950. It was close to Daejeon, where UN troops had lost the Battle of Taejon in mid-July. On Aug. 25, Maj. Gen. William F. Dean, commander of the US Army’s 24th Infantry Division, was taken prisoner by the North Koreans.

The US Army left behind trucks filled with firearms and bullets. “I got in and played with those guns that they left behind,” my father recalls. But food was scarce. “You can’t imagine. We had nothing, nothing to eat.”

My grandmother came up with a desperate plan: She would send the older children back to Chuncheon on their own, in hopes that their house would still be standing, even though the city was occupied by the North Koreans.

One August morning, the children set out on foot. They walked for a full day, eventually finding a family willing to take them in for the night.

“We cried all night, all of us,” my father recalls. “And then we decided: Well, if we’re going to starve to death, we want to go back and die with Mom.”

They returned to Okcheon to find their mother sobbing on the veranda. Gathering them in her arms, she told them: “If we die, we die together.”

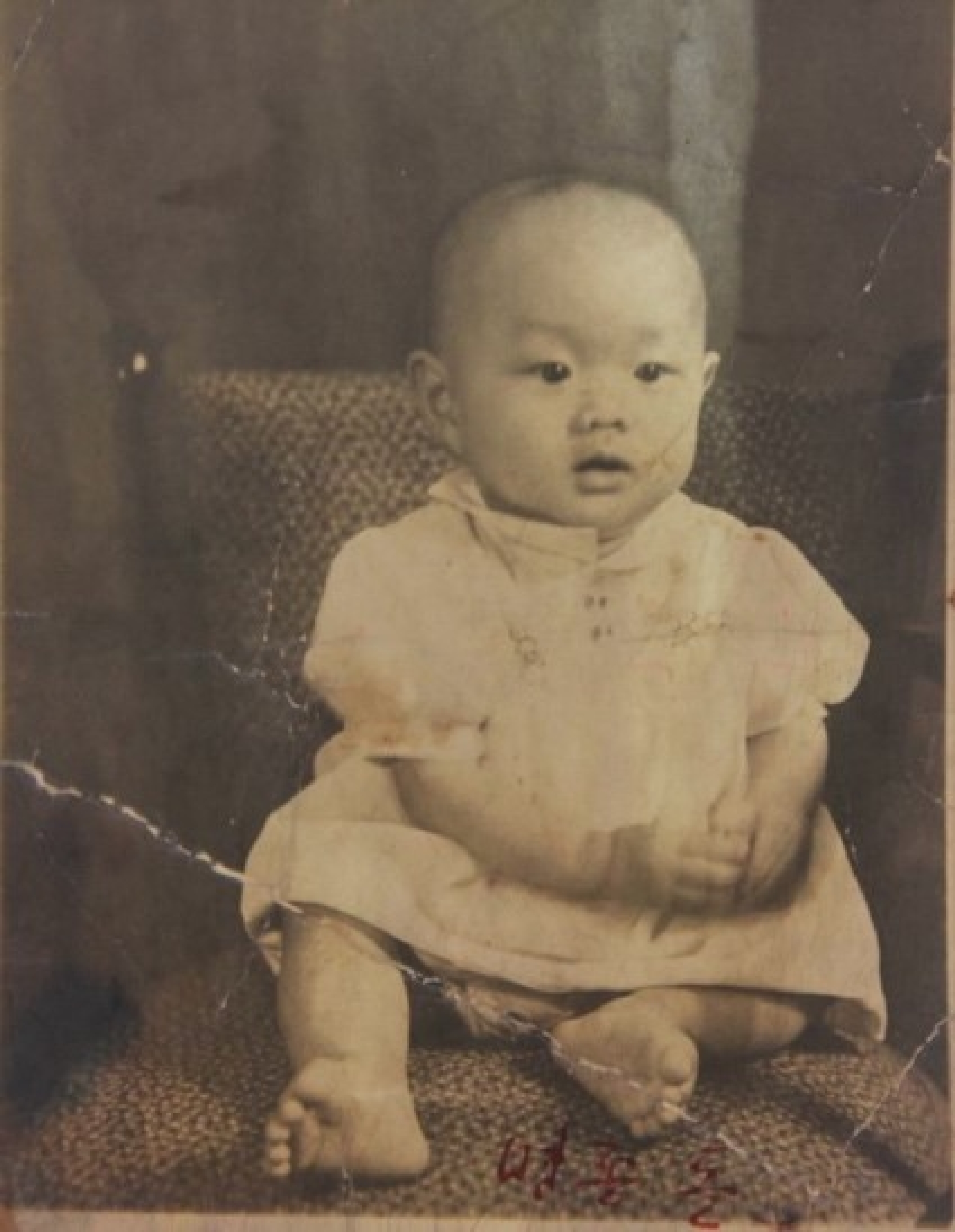

The dangers were not all found in the conflict. The older children knew to avoid the nuts from the ginkgo trees in the backyard, which can be toxic. But the youngest, Geun-jong, could not resist. The older children watched helplessly as the toddler began vomiting and then convulsed in the courtyard.

He was dead by morning. “What could we do? Nothing," my father recalls.

“We cried all night, all of us,” my father recalls. “And then we decided: Well, if we’re going to starve to death, we want to go back and die with Mom.”

Geun-jong’s death plunged my grandmother into grief. Very much a traditional Korean woman, she never allowed herself to be seen without her hair in a bun. But when her youngest died, she let her hair down.

It was a sight that sparked panic in my father, then 10. “I saw her walking to the mountain in back [of the house], so I followed her for fear she was going to commit suicide,” he recalls.

She returned safely after a respite in the mountains, to his relief.

Inchon and Beyond

In September 1950 came news of a daring amphibious assault by the US Marines at the port of Incheon west of Seoul. Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s bold intervention, known as the Inchon Landing, allowed UN troops to regain control of nearby Seoul and push the North Koreans back up the peninsula.

My grandfather and his two older sons emerged from hiding and rushed to Okcheon.

“We expected our little Geun-jong to run out first to meet us, but he wasn’t with the family. We quickly sensed something wrong, but nobody said a word,” Uncle Hank wrote.

The family had buried Geun-jong without a funeral or tombstone.

“After a moment, my father broke the silence by saying that Geun-jong took all our misery and suffering with him, and left us alive and well through his sacrifice,” he recalled. “We all cried, even my father had tears in his eyes, maybe more for losing the little brother GJ than for joy of our reunion.”

They continued on to Seoul to find their home completely destroyed. Neighbors told them the North Koreans had seized the property and installed an anti-aircraft machine gun on the roof. A UN fighter jet obliterated both the gun and the three-story home.

The family’s big house in Chuncheon had fared no better. The North Koreans had turned it into a regional headquarters, and it was destroyed in an air raid. My family lost everything in those first few months of war.

As the UN troops crossed the 38th Parallel and seized Pyongyang, the Lees began rebuilding their lives in Seoul. They thought the war would be over soon.

The family’s big house in Chuncheon had fared no better. The North Koreans had turned it into a regional headquarters, and it was destroyed in an air raid. My family lost everything in those first few months of war.

But in October 1950, the Chinese joined the war, cornering the US Army’s X Corps with a sneak attack in Jangjin, North Korea, in what is known by the Japanese-era name as the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir. Encircling tens of thousands of UN forces in a brutal fight in late November and early December, Chinese troops forced them to retreat below the 38th Parallel again – and retook Seoul.

It was a dangerous time to be a young man in the South Korean capital.

One day, my father tells me, an uncle, who was a newly married veterinarian, stepped out of the house to run a quick errand. His wife later learned he had been seized by the North Koreans. Two other uncles, a physician and a diplomat, also disappeared. Both were leftists, my father recalls, and may have joined the North Koreans voluntarily, he says.

The family never saw or heard from them again.

The Rats of Busan

In January 1951, the Lee family fled south once again, this time during a bitterly cold winter and with a new baby, my Aunt Young-shim, in tow. They bribed their way onto a freight train and sought refuge in the southwestern port city of Busan along with nearly all of Seoul.

All ten of them squeezed into one ramshackle room that served as kitchen, living room and bedroom until my grandfather could find them a proper house. “Terrible” is how my father remembers it, with everyone in the shantytown sharing an outdoor toilet where the waste spilled into the street.

When asked about that room, both my father and my Uncle John said the same thing: “Rats everywhere.” They even dropped from gaps in the ceiling.

Eventually, their father was able to secure a more comfortable home in Busan. My father remembers holding his own among the local Busan bullies at elementary. Uncle Hank wrote about tuning into the Armed Forces Network radio to learn English, and falling in love with the music of Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, Eddie Fisher, Tony Bennett and Doris Day.

He was already on his way to becoming an American.

All ten of them squeezed into one ramshackle room that served as kitchen, living room and bedroom until my grandfather could find them a proper house

As the fighting continued, representatives from North Korea and China began meeting in July 1951 with counterparts from the United States and the United Nations to negotiate a cease-fire. Those talks stretched on for two years until an armistice agreement was signed on July 27, 1953.

News of a truce arrived on my father’s 13th birthday. The Lee family left Busan and returned to a devastated, demolished Seoul. Amid the rubble, the Lees resettled in Changseong-dong, next to Gyeongbok Palace in Seoul, and focused on rebuilding their lives.

New Lives, New Americans

With South Korea in ashes, my grandparents set their sights on sending their sons off to America to be educated. Uncle Hank left for Dudley, Massachusetts, the following year, and John and YC soon followed him to the United States. Eventually, five of my grandparents’ eight surviving children, including my father, became US citizens, raising the next generation here as Americans.

We children of those Korean War “peasants” became doctors, journalists, economists, professors, musicians, fashion designers and CEOs, making our family story not just a Korean War memory but also an American tale. We are proof that the defense of South Korea was worthwhile. (For a truly astounding Korean-American tale, read The Great Leader and the Fighter Pilot, by Blaine Harden.)

Today, my father’s story has come full circle. After 30 years in the United States working as a neurologist, he returned as a U.S. citizen to a South Korea that he did not recognize in 1991. He has since regained South Korean citizenship, making him and my mother dual nationals. They live not far from Chuncheon, the city of his birth, though the wreckage of the house that the North Koreans occupied has long since made way for downtown office buildings.

My father turns 80 this year. And it is only now that I have asked him what happened when the Korean War broke out 70 years ago.

It is an awkward conversation, so many years late. In many Korean families like mine, we rarely discussed the war growing up, choosing instead to bury the most difficult memories and to focus on moving forward. That’s how Korean families survive.

But my work as a journalist has taken me to enemy North Korea dozens of times. So I think constantly about the Korean War and the impact it still has on geopolitics in Northeast Asia today.

It is not often that we mark the start of a conflict; we typically celebrate their end. However, this is a war that has not formally ended. There has been no peace treaty. To call it a Forgotten War is ironic, because it is a conflict that is very much alive — in North Korean ideology and propaganda, inside the Demilitarized Zone, and in the faltering diplomacy between North Korea and the United States.

We children of those Korean War “peasants” became doctors, journalists, economists, professors, musicians, fashion designers and CEOs, making our family story not just a Korean War memory but also an American tale.

To forget about this war is irresponsible; remembering is the key to understanding. We cannot negotiate peace and stability without understanding and resolving the conflicts and resolutions of the past.

For me, remembering what happened in 1950, and in the years that followed, is essential to understanding what shaped my father’s life — and, ultimately, mine.

Jean H. Lee is Director of the Hyundai Motor-Korea Foundation Center for Korean History and Public Policy at the Wilson Center, and a former AP Seoul bureau chief who also opened the news agency’s bureau in Pyongyang.

(Cover photograph: Battle-weary Korean civilians crowd a road seeking safety from the continuous fighting in January, 1951. UN Photo.)